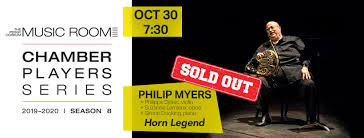

PHILIP MYERS

PHILIP MYERS

ENGLISH & FRANÇAIS:

Phil Myers, every Horn player on the planet, knows that you were Principal Horn of the NewYork Philharmonic, arriving there in 1980. But have you been appointed somewhere else before?

Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada 1971-1974 1st horn

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, US 1974-1978 3rd horn

Minneapolis, Minnesota, US 1978-December 1979 1st horn

Then New York starting in January 1980

In the early 80's you were already professional, during your studies, when came the wish to be a high Horn and specifically Principal?

Never. I had realised that 95% of a horn player’s job was accompaniment, that if one was waiting for the next solo that one would be spending most of their time waiting. So my life was spent making the accompaniment my main interest. This can be done equally on 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th. Also, only when I was 20 years old, could I play above G? From nine years until 20 I could not really play the high range so I knew that first horn was not really a possibility. Then my teacher got very angry with me that I was not doing what he told me, so I promised that I would and 4 months later I had a higher octave to high G above high C. Then I knew that at least I could audition also for high horn positions. 1971: Chicago associate 1st horn (they wanted me to play softer, I did not have control of dynamics at age 22) lost

Toronto 2nd horn (they rejected my application, a friend got me into the audition, I embarrassed myself) lost

Halifax 1st horn (I played as well as I could) won

1972 or 1973: Denver 1st horn (worst audition I ever played) lost

Winnipeg 1st horn (committee sat close, made me afraid, played badly) lost

(hadn’t figured out yet that the committee is used to hearing you close in the orchestra so you don’t have to play differently - I was sort of slow to figure things out) lost

Toronto 2nd horn again (the only thing I remember about this audition is that they begin laughing when I was sight-reading a Hindemith excerpt) lost

Ottawa 1st horn (I called my teacher after this audition and when he said “Hello” I was so choked up with sadness that I couldn’t speak. He thought someone had called him and hung up.) lost

The Ottawa audition was the turning point. I was so disappointed that I resolved to take a different approach to auditions.

1974: New York associate 1st (this was the first audition that I felt I had played 1/2 the excerpts that way I wanted to) lost

Pittsburgh 3rd horn (felt very comfortable in this audition) won

1976: Philadelphia (assistant 1st, 2nd, 4th) (I reverted to my former approach and played badly) lost

This audition was very disappointing for me. I had failed to use my new approach and had played badly as a result. I promised myself I would never do this again in an audition and I kept that promise.

1976: Dallas 1st horn (this is the best audition I ever played - they offered me the job, I could not get released from my contract for a year and the manager decided not to wait, but they hired instead a horn player that I have always had a lot of respect for, Gregg Hustis)

1977: Minneapolis 1st horn (played welled, missed the C#’s in Haydn 31 but otherwise felt pretty good) won (loved this orchestra, very happy 1.5 years) (they waited a year for me to come) It was a great section and orchestra and I liked very much working with Stanislaw Skrowaczewski for the first year and then Sir Neville Marriner for four months before leaving for New York.

1979: New York 1st horn (This long story: went to play the audition, did not play so well, apologised to James Chambers, the personnel manager and former 1st horn after the audition for playing so badly. I told him that there many of us that admired his playing and career. He told me that there was nothing that he had heard in the 25 auditions that day that made him feel that way. The player that the committee liked the most that day was a 22 year old horn player named Jerome Ashby but Zubin Mehta, the music director, was simply afraid to hire someone 22 years old for principal. He went to their committee and the personnel and told them that there were six players that he wanted to have play for the principal job in a second audition based on what he had heard of them.

I was one of those people, I won the second audition (felt very comfortable that day) and the 22 year old, Jerome Ashby, become the associate 1st as that position was also open.

Was your path of studies full of great examples to follow (I mean listening other talented hornists) or mostly all the time, you had to improve yourself as a pioneer?

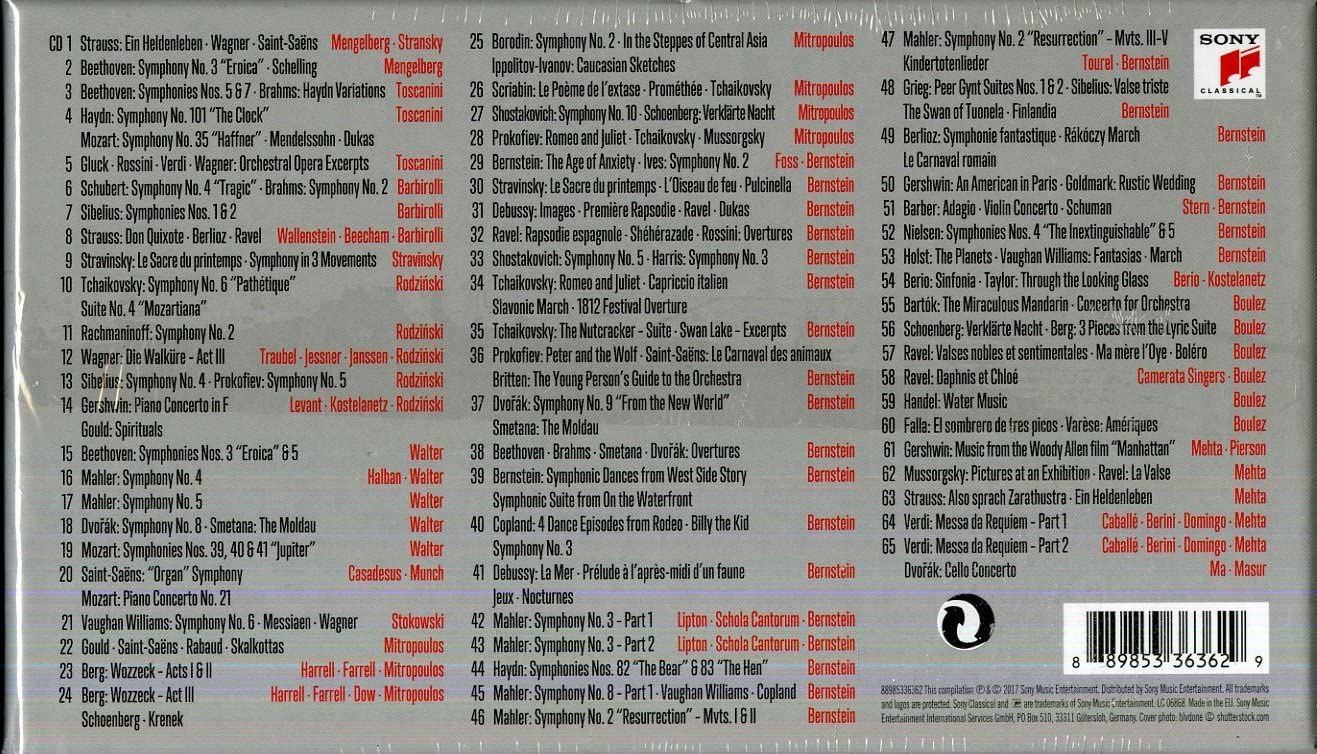

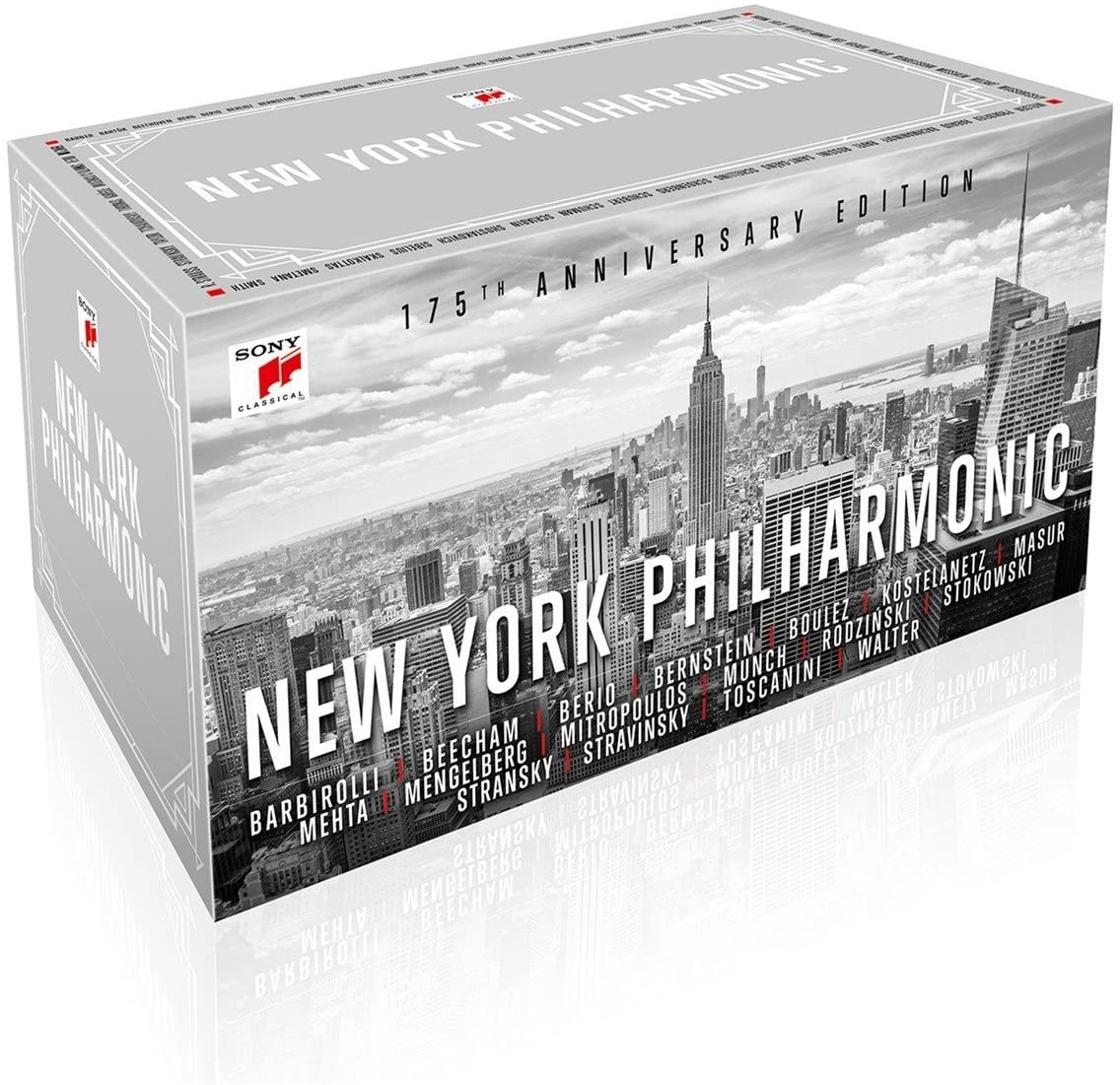

One story: When I got to the New York Philharmonic one of the first things we were going to play was Brahms First Symphony. I had never played it. This really isn’t ok if you are the first horn of a major orchestra so I was concerned/scared. I did not want to make a fool of myself. I had 13 recordings of the piece in my house. I sat down one night and listened to all of them (yes, all night). When I went into the first rehearsal I copied one guy for this part, a different guy for a different part. I had just picked out all my favourite parts and copied those. That how I started my career, copying other people. Still I cannot play the Mozart concertos without hearing Dennis Brain in my mind. For the call in the last movement of the Brahms 1st, I copied James Chambers with the New York Philharmonic because I liked the weight that he gave to the sixteenths. Second movement: no contest, Myron Bloom, first horn of the Cleveland Orchestra and Orchestre de Paris.

In my opinion Myron Bloom is the greatest musician to ever play the horn. I have every recording he ever made and if I hear a piece in my head that both he and I recorded, I hear him playing it, not myself. I studied with him and he changed my life.

Back to NY PHIL, I think that no one can imagine the psychological pressure of being Principal Horn in this orchestra. Could you give us some tips about how you were managing so well this aspect?

I consider that in my career I was extremely fortunate that for almost fifty years I never had a note counter as a music director.

Klaro Mizerit

William Steinberg

Andre Previn

Stanislaw Skrowaczewski

Zubin Mehta

Kurt Masur

Lorin Maazel

Alan Gilbert

Everyone one of them would rather hear you try to do something extreme (staccato, legato, fff, ppp, etc.) that do the same thing that they had heard in some other orchestra. There are some very good horn players who never had this supportive experience with their music directors. I was lucky.

Are the great conductors (I mean famous names) mostly helping through their obvious qualities, or are they frequently putting pressure, even unknowingly?

Never. Bad conductors always tell you what you SHOULD NOT do, good conductors always tell you what you SHOULD do. That is much more positive and easier to do, I think. So really, the better the conductor, the less the pressure.

In a top quality orchestra like NY PHIL, are the colleagues helping the Principal, as often as they can, or are they just busy, trying their best to manage their own part? (I mean in the dynamics in order to save your lips, things like that...)

I think one of the regrettable things (and I do not like to talk about sad things) in my orchestral life was to see respect replaced by jealousy.

When I first joined the orchestra business, if a great violin soloist came to play with the orchestra (I remember Henryk Szeryng coming to Pittsburgh) and they received respect. Musicians talked about what was special about what the musician was doing. As time went on in my fifty years, it seemed as though jealousy replace respect.

A great violin soloist would come to town and the musicians would be talking about their failings instead of their uniqueness. This was saddening to me because without someone to respect, what is their to strive for?

In a normal time, how long before a project were you preparing the program?

In 1982 we were going to play Konzerstuck for the first time since I had been in the New York Philharmonic. I decided to borrow a horn from Chuck Kavolovsky, the first horn of the Boston Symphony. I had gone to hear him play the Konzerstuck in Boston and it sounded so easy for him and the quartet entirely. I was very impressed. So when we were going to play it in New York I called Chuck and ask him if I could borrow that horn. He said yes. So my girlfriend at the time and I drove up to Boston and when we went into his practice room on the stand was Cherubini Two Sonatas. This was October. I asked “are you playing it”, he said “yes, in May.” Well, I have to tell you that as a 32 year old I have never practiced anything for six months. Now I am 70, I like to know a year in advance. Things change with age.

By the way, he loaned me his Paxman Bb-high Bb and while it got the notes fine, I could not play very loud on the high Bb side at that time. This bothered the second horn player (Rainer DeIntinis) very much but there was only so much I could do. Last time I played it on the high Bb horn.

For years, you also went to the Israel Philharmonic for doing weeks there as guest. Actually, once at Marcus Bona's factory, he told me doing a special case yours in order to travel around the world with 2 horns! Was this experience a quite easy job, super trained as you were, or at the contrary not being living there, was it more a constant challenge? (because of travel, visa, jet lag...)

No, no, only one time did I play with the Israel Philharmonic and that was when they were on tour in New York. The first horn player was Yaacov Mishori and I was to play assistant first horn on the Mahler Symphony No. 5 and principal on Bruch Violin Concerto which I always loved to play. I asked Zubin why he wanted me to play this concert (he had enough horn players with him) and he said “I want them to hear your approach, what is different and what is the same.” So I figured that I should play as I typically played in the tutti because of course I was playing none of the solos. Every conductor has his own unique traits and for some reason, both in New York and in Israel, he did not feel comfortable with the way the horns started the third movement with its little accelerando.

Zubin told me he wanted me to play those first few measures even though it is not in the first horn part. A day before the concert they told me that there would be a sectional for the horns before the concert with the assistant conductor (I do not remember his name) and for thirty minutes every time I played a note he told it was horrible.

In big orchestras it is very hard to get direct feedback from anyone about what you are doing wrong (including the conductor) because they do not want to offend you. As I sat there in the rehearsal before the Israel concert I thought to myself, «Wow, this may be the last time I ever get really direct, honest, negative feedback from someone». It did not offend me, I thought it was great the guy was just saying exactly what he thought.

Unfortunately, between the rehearsal and the end of the concert someone had told him that I was the first horn of the New York Philharmonic so he came to me at the end of the concert and apologised.

I felt sad, I told him I was grateful for his feedback. And I was. Unfortunately I was wrong about honest negative feedback. Kurt Masur had plenty.

Nearly 10 years ago, you started teaching in Switzerland, while still playing in NY PHIL as a regular member. How did you like doing that kind of big jump between 2 continents (and their differences)?

I had been used to 36 weeks playing in the Philharmonic, 16 weeks off. Now it was 46 weeks on, 6 off, plus I was away from my wife for 10 weeks. So it was a lot less time to go other places to play, now instead I was teaching in Switzerland.

1) I was grateful to have been asked to teach in Fribourg, CH.

2) I said to my wife that we would try it for a year and then have a talk about whether being apart for those ten weeks was bad for our relationship.

No, she told me it was no problem (?). Now, we have been together for 21 years and are very happy. I wonder if she is going to wish for those 10 weeks not that Maestro Jacques Deleplanque has replace me.

I’ll let you know.

In 1995, we have been "sharing" the stage during the Horn symposium in Bordeaux. we were really mixing our pieces, and I saw you drinking coke backstage! But you impressed me so much with your fantastic playing, using for example an incredible range of dynamics. In that case, are you practicing before in the exact same dynamics (even in a small room) or the concert hall there in Bordeaux pushed you to improve yourself for a nicer performance?

First of all, this was the greatest horn conference I ever attended for many reasons.

1) I had just gotten a divorce and I needed diversion.

2) I was there with my best friend since 1978, Howard Wall and I loved playing with him in some of these recitals.

3) The host was the nicest person, Joseph Hirschowitz - took us to many vineyards.

4) Ordered my first Schmid french horn - had met him a couple of years later, the articulation response seemed better to me. I was going to buy the descant but Howard told me I sounded better on the full triple high F so I bought that. I practiced on that horn today (13/06/2020)

I have always trusted my friends more than myself when it came to buying horns and mouthpieces.

In Germany at the Schmid Horn Days (2018), we all were teaching the full day, but at some point we were all stopping except you. How do you explain this inner passion you have to share your knowledge in a such concentration that you are able to proceed without thinking to stop?

Fear of the future of curiosity. I never felt a burden of practicing myself because always it was a quest to satisfy my curiosity.

My to main fields of curiosity

1) how to play the horn technically

2) the structure of music phrasing.

If any student showed an interest in music and especially these special areas of interest to me, then I was willing to share with them what I thought I had been shown forever.

There are not so many curious students ever, not just the last few years, ever. When you meet them, you must give them everything you have.

If you have curiosity, you do not need discipline.

Speaking about auditions in NY PHIL, it sounds strange from Europe that almost every round is without piano accompaniment. Please tell us why and also if this is common in the USA.

Yes, it is true, usually we are only using the piano in the final round.

I think that the idea here is this. Auditions are to hear if someone can PLAY, the probation period in the orchestra (usually 17 months) is to hear if someone can LISTEN. The only function of the piano therefore would be to see if someone could listen and we didn’t find that it told us enough about someone's listening to matter.

For instance, take the second horn solo at the beginning of Mahler’s Symphony No. 9. In the audition we can hear how they can PLAY stopped horn loudly, pp, p, etc.

In the orchestra we find out if they LISTEN to what is going on around them and interact with it.

Do we hear

1) interruption of the calmness of the first six bar phrase with the loud stopped measures.

2) accompaniment of the violins (in sync) measures 7-10

3) answering the violins statement (opposed) measures 11-14

4) now making the statement with the violins answering (opposed) measures 15-17 (things have reversed)

One time playing through this in an orchestra rehearsal and you can hear if the new probationary second horn knows, hears and responds to these things. I think our experience here is that having someone play with a piano in the audition just doesn’t tell us enough

no matter how sophisticated the interaction.

First time I heard NY PHIL was in Paris Salle Pleyel probably in the 90's, Zubin Mehta conducting. Great Schubert 3rd symphony played generously Jerome Ashby as first, then spectacular Rite of Spring played by you (so laut and clean, without bumper!!!) then as encore a piece by Duke Ellington arranged for orchestra, where Jerome did some solos. Do you remember this tour?

Thirty years after Zubin left the orchestra we still played it as he conducted it no matter who was conducting because his interpretation was so sound. The part I remember especially was at the end rehearsal 192. The third and fourth measures he wanted fairly emphatic. Then at rehearsal 193 to 196 it became the most relaxed and joyful waltz. It absolutely felt as comfortable as playing in 3/4 even though the meter is uneven. We did the Rite of Spring

a lot with him as well as Mahler Symphony No. 5. We used to joke that we played these pieces on tour because everyone had them memorized so they didn’t have to bring the music.

The European tours were always a good time because the orchestra had been there so many times that you knew the sites you wanted to go back to, you knew the shops, and you knew the hotels and restaurants (and in France, the cheese). So there was an unusual level of comfort on those tours because people felt almost at home. And they knew the acoustics of the halls in advance, from before, so also this made things comfortable.

Most of the people after their working life are thinking about what they could have done differently, for a better life. When one reach for the moon, what can he dream of?

1) Gratitude for what one was given.

2) I don’t think any old person does not wonder about the meaning of life, no matter what their profession. There is no answer!

3) One of the best non-musical thoughts I was ever given was this question: “Would you rather be right or happy.”

I think we all want to be “right” but for me it rarely led to happiness. Now I just try to he happy.

Coda: Maestro how do you see Classical music in our society in a half century from now ?

For a mathematician, 2+2=4 is an emotional event. Because it is so, he becomes a mathematician. For me, the horn has a physical implication/meaning and the structure of music (am I dignifying it or fighting it) has an emotional implication.

As long as performing musicians feel this emotional meaning, they will be able to communicate it to the audience and classical music will exist.

If we get to a place where performers themselves do not feel very much emotional reaction to music, then we are done, it will not survive.

JUNE 2020

FRENCH SPEAKING/EN FRANÇAIS:

Phil Myers, les cornistes du monde entier savent que vous avez été Cor Solo du Philharmonique de New York pendant des décennies. Mais avez-vous été nommé ailleurs auparavant?

Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada 1971-1974 1er cor

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, US 1974-1978 3ème cor

Minneapolis, Minnesota, US 1978-December 1979 1er cor

puis New York, débutant en Janvier 1980

Dans les années 80, vous étiez déjà professionnel, mais avant, quand vous est venu l’idée d’être cor aigu et particulièrement cor solo?

Jamais. J’avais réalisé que 95% du boulot d’un corniste était l’accompagnement, et que si on attendait le prochain solo, on passerait la plupart de son temps à attendre! Donc dédier ma vie à faire de l’accompagnement mon principal intérêt. Cela peut être le cas aussi bien au 1er, 2ème, 3ème, 4ème cor. En outre, seulement quand j’avais 20 ans j’ai pu jouer au-dessus du sol aigu. De neuf ans jusqu’à 20, je ne pouvais pas vraiment jouer dans le haut de la tessiture, donc je savais que le premier cor n’était pas vraiment possible. Puis mon professeur s’est mis très en colère contre moi car je ne faisais pas ce qu’il me disait, alors j’ai promis que je le ferai et 4 mois plus tard, j’avais gagné une octave à partir du sol aigu, allant au-delà du contre-ut! Ensuite, j’ai su que je pourrai aussi au moins auditionner pour des positions de cor aigu. -1971: 1er cor assistant à Chicago (ils voulaient que je joue plus piano, je n’avais pas le contrôle des nuances à 22 ans) perdu.

-Toronto 2ème cor (ils ont refusé mon inscription, un ami m’a porté quand même au concours à mon grand embarras) perdu

-Halifax 1er cor (j’ai joué du mieux que j'ai pu) gagné

-1972 ou 1973: Denver 1er cor (pire concours de ma vie) perdu

-Winnipeg 1er cor (le jury s'est assis très près ce qui m’a fait peur, j’ai mal joué) Je n’avais pas encore compris que le jury peut être proche, un peu à l’image des musiciens dans l’orchestre, donc cela ne sert à rien de jouer différemment. Je manquais de clairvoyance sur ces choses-là. perdu

-Toronto 2ème cor de nouveau (la seule chose dont je me souviens à propos de ce concours est qu’ils ont commencé à rire quand j’ai déchiffré un passage d’Hindemith. perdu

-Ottawa 1er cor (j’appelle mon prof. après l’audition, et quand je dis «allo», je suis pris d’une réaction de tristesse qui fait que je ne peux parler. Il pense alors que quelqu’un a téléphoné pour raccrocher…) perdu

Ce concours fut un tournant. J’étais tellement déçu que je me suis résigné à avoir une autre approche des concours.

-1974: New York assistant 1er (cette audition, j’ai senti que j’avais joué à la moitié des mes attentes). perdu

-Pittsburg 3ème (me suis senti à l’aise dans ce recrutement) gagné

-1976: Philadelphia (assistant 1er, 2ème 4ème) je suis revenu à mon ancienne approche et j'ai mal joué. perdu

Ce concours me fut très contrariant. Je n’ai pas réussi à utiliser ma nouvelle approche et au final, je n’ai pas bien joué. Je me suis juré que cela n’arriverait plus et m’en suis tenu à ma promesse.

-1976: Dallas 1er cor (c’est la meilleure audition que j’ai jamais faite) - ils me proposèrent le poste, mais ne pouvant pas prendre un congé d’un an, le directeur n’a pas voulu attendre, ils ont pris à ma place, un corniste que j’ai toujours admiré, Gregg Hustis).

-1977: Minneapolis 1er cor (j’ai bien joué, mais j’ai raté le do dièse de la symphonie n. 31 d’Haydn, sinon je me suis bien senti) gagné. J’ai adoré cet orchestre, j’y fus très heureux un an et demi. Ils m’avaient attendu un an avant ma prise de fonction. C’était un super pupitre et orchestre. J’ai beaucoup aimé travailler avec Stanislaw Skrowaczewki la première année, puis avec Sir Neville Marriner pour 4 mois avant de partir pour New York.

1979: New York 1er cor (c’est une longue histoire, je suis allé faire ce concours, je n’ai pas très bien joué, je m’en suis excusé auprès de James Chambers (et du DRH et du précédent cor solo). Je lui ai dit que beaucoup d’entre nous admiraient son jeu et sa carrière. Il m’a dit qu’il n’y avait rien chez les 25 auditionnés ce jour-là qui lui faisait ressentir un tel niveau. L’instrumentiste le plus apprécié ce jour fut un garçon de 22 ans, appelé Jerome Ashby, mais le directeur musical Zubin Mehta a eu peur d’engager un jeune de 22 ans comme cor solo. Il est allé vers la commission et l’administration et leur a dit qu’il y avait 6 personnes qu’il voulait réécouter pour le poste de 1er cor. J’en faisait partie, je gagnais la seconde audition (me suis senti bien ce jour) et le jeune de 22 ans Jerome Ashby devint «associé au 1er» car le poste était libre.

Votre parcours fut-il plein d’exemples à suivre (j’entends avoir eu l’occasion d’écouter d’autres talentueux cornistes) ou avez-vous eu plutôt le sentiment d’ouvrir la voie seul tel un pionnier?

Une histoire: quand j’ai remporté le Philharmonique de New York, une des premières séries incluait la 1ère symphonie de Brahms. Je ne l’avais jamais jouée. Cela ne va pas quand tu es cor solo d’un orchestre de première catégorie, aussi j’étais concerné mais aussi apeuré. Je ne voulais pas me ridiculiser. J’avais 13 enregistrements de cette oeuvre chez moi. Je me suis posé une nuit, et j'ai commencé à les écouter tous (oui, toute la nuit!) Quand je suis arrivé à la première répétition, j’ai imité quelqu’un pour tel passage, quelqu’un d'autre pour tel autre passage. J’avais juste pris tous mes passages favoris et les avais copiés. Voilà comment j'ai commencé ce job. en copiant d’autres personnes. Encore aujourd’hui je ne peux jouer les concertos de Mozart sans avoir Dennis Brain dans l’oreille. Pour l’appel du Final de la 1ère de Brahms, j'ai copié James Chambers avec le NY Phil, car j'aimais le poids qu'il mettait sur les doubles. Dans le 2ème mouvement, sans équivoque, Myron Bloom, premier cor de l’orchestre de Cleveland et de l'Orchestre de Paris. A mon avis, Myron Bloom est le plus grand musicien qui ait jamais joué du cor. J’ai tous les enregistrements qu'il a pu faire, et si j'ai dans la tête, une pièce que lui et moi avons tous les deux enregistrée, c'est lui que j’entends jouer, pas moi. J'ai étudié avec lui et il a changé ma vie.

À propos du Philharmonique de New York, je suis convaincu que personne ne peut imaginer la pression ressentie à assumer le rôle de 1er cor solo. Pouvez-vous nous donner les secrets de votre réussite?

Je suis conscient que durant ma carrière, j’ai eu la chance que pendant près de 50 ans, je n’ai jamais eu de chefs d’orchestre besogneux.

Klaro Mizerit

William Steinberg

Andre Previn

Stanislaw Skrowaczewski

Zubin Mehta

Kurt Masur

Lorin Maazel

Alan Gilbert

Chacun d’entre eux préférerait vous voir essayer de faire quelque chose de particulier (staccato, legato, fff, ppp, etc.) que vous entendre faire la même chose que dans d’autres orchestres. De très bons cornistes n’ont jamais eu l’occasion de bénéficier du soutien de leurs directeurs musicaux. Je fus chanceux.

Est-ce que les grands chefs (je veux dire les noms connus) aident généralement ou bien mettent souvent plutôt la pression, même inconsciemment?

Jamais. Les «petits» chefs disent toujours ce qu’il ne faut pas faire, alors que les bons chef disent ce qu’il faut faire. C’est beaucoup plus positif donc facile. Aussi disons que meilleur est le chef, moins tu as de pression.

Dans un orchestre de niveau international comme le Philharmonique de New York, est-ce que les membres du pupitre aident le 1er aussitôt qu’ils le peuvent, où sont-ils suffisamment occupés à assumer leur partie à ce degré d’exigence? (j’entends dans les nuances pour qu’il s’épargne les lèvres, etc…)

Je pense que l’une des choses regrettables dans ma vie au sein de l’orchestre (et je n’aime pas parler de choses tristes) fut de voir le respect remplacé par la jalousie.

Lorsque je me suis joint à cette machine qu’est l’orchestre, si un grand violoniste soliste venait jouer avec l’orchestre (je me souviens d'Henryk Szeryng à Pittsburgh), ils étaient respectés. Les musiciens parlaient des choses spéciales que faisait le musicien. Au fil des cinquante années que j’ai passées, j’ai l’impression que la jalousie a remplacé le respect. Un grand violoniste soliste venant chez nous, les musiciens vont parler de ses défauts au lieu de son unicité. C’était triste pour moi parce que sans quelqu’un à respecter, à quoi bon?

En temps normal, combien de temps preniez-vous afin de monter un programme?

En 1982, nous allions jouer pour la première fois le Konzertstück depuis mon arrivée au NY Phil.. J’ai décidé d’emprunter un cor à Chuck Kavalovski, le 1er cor du Symphonique de Boston. J’étais allé l’écouter dans cette pièce à Boston, et il semblait jouer si facile, lui, mais aussi tout le pupitre. Donc quand on s’approchait de la date du concert à New York, j’ai appelé Chuck pour lui demander s'il pouvait me prêter ce cor. Il a accepté. Alors mon amie de l’époque et moi partons pour Boston et quand on s’est trouvés dans sa loge de travail, sur le pupitre il y a fait les 2 sonates de Cherubini. C’était en Octobre. Je lui demande, «vas-tu jouer cela», il répond «oui, en Mai». Bien, Hervé je dois t’avouer qu’à 32 ans, je n’ai jamais rien travaillé pendant 6 mois! Aujourd’hui, j’ai 70 ans, j’aime connaître mes pièces un an avant. Les choses changent avec l’âge.

À propos, il m’a prêté son Paxman en Sib-Sib aigu, mais quand les notes étaient là, je ne pouvais pas jouer fort à cette époque sur le cor en Sib aigu. Cela troublait beaucoup le 2ème cor Rainer Dentines (1925-2008), mais il n’y avait pas grand chose à faire. Ce fut la dernière fois que je l’ai joué sur un cor en sib aigu.

Vous êtes allé en « guest » jouer au sein du Philharmonique d’Israël pendant des années. D’ailleurs un jour chez Marcus Bona à San Paolo, il me dit créer un étui spécial pour vous afin d’emporter 2 cors ensemble. Cela fut-il facile car vous étiez entrainés au plus haut niveau, ou bien n’étant pas là-bas souvent, était-ce un vrai challenge? (à cause du voyage, visa, décalage horaire…)

Non, non, la seule fois que j’ai joué avec le Philharmonique d’Israël, il s’agissait de leur tournée à New York. Leur premier cor était Yaacov Mishori, et je devais l’assister au 1er dans la 5ème de Mahler et jouer le premier dans le concerto pour violon de Bruch (que j’ai toujours adoré jouer) J'ai demandé à Zubin (Mehta) pourquoi il me voulait (il avait assez de cornistes), il m’a dit «je veux qu’ils entendent ta vision, ce qui est différent et ce qui est pareil». J’ai induit que je devais jouer comme «à la maison» car de toutes façons, je ne jouais aucuns des solos. Chaque chef à sa vision de tel ou tel passage, et curieusement que ce soit à NY Phil ou Israël Phil, il ne se sentait pas bien avec la façon dont les cors attaquaient le début du 3ème mouvement et son petit accelerando. Zubin me demanda de jouer le tout début sachant bien que ce n’est pas écrit au 1er cor. La veille du concert on m’avisa qu’il y aurait une partielle de cors le jour du concert, dirigée par l’assistant (je ne me rappelle plus son nom). Pour une demi-heure à chaque fois que je jouai une note, ce chef me disait que c’était moche.

Dans les grands orchestres. c’est difficile que quelqu’un vous dise ce que vous faites mal, (même le chef), parce que à ce niveau ils ne veulent pas vous offenser.

En m’essayant pour la répétition d’avant concert, je me dis. Alors là, c’est sûrement la dernière fois que j’entends quelqu’un me parler aussi directement, honnêtement, d’un retour aussi critique. Cela ne m’a pas vexé, je me suis dit cet homme a juste essayé de dire exactement ce qu’il pensait. Malheureusement entre la répétition et la fin du concert quelqu’un est allé lui dire que j’étais 1er cor au NY Phil, donc il est venu me voir à la fin pour s’excuser. Cela m’a attristé, je lui ai dit être reconnaissant pour ses réflexions. Et je l’étais. Malheureusement je me trompais sur ces commentaires faits en toute bonne fois. Kurt Masur en a eu plein…

Il y a environ 10 ans, vous avez commencé à enseigner en Suisse, tout en continuant votre poste d’orchestre. Comment avez-vous vécu ces sauts entre 2 continents et leurs différences culturelles?

Pendant des années, j’avais 36 semaines d’orchestre et 16 libres. Maintenant c’est 46 semaines de travail, et 6 libres. En outre je quittais ma femme 10 semaines par an (pour la Suisse). Cela ne laissait plus de temps pour aller jouer ailleurs car j’avais ces cours en plus.

1) J’ai été reconnaissant d’avoir été sollicité pour enseigner à Fribourg.

2) J’avais dit à ma femme on va essayer pour une saison puis nous parlerons pour savoir si le fait d’être séparé pendant ces 10 semaines était mauvais pour notre relation.

Non, elle m’a dit c’est sans problème (?). Maintenant, cela fait 21 ans qu’on est ensemble, et nous sommes très heureux. Je me demande si elle va souhaiter pour ces 10 semaines, que le maître Jacques Deleplanque ne me remplace pas.

Je vous le ferai savoir.

En 1995, nous avons partagé un récital durant le congrès International de Bordeaux. Nous alternions nos pièces et je vous voyais boire des canettes de Coca Cola! Vous m’avez tellement impressionné avec votre jeu, par exemple en utilisant une large gamme de dynamiques. Vous étiez-vous entrainé à cela (même dans une petite salle de travail), ou bien la salle de Bordeaux vous a-t-elle conduit à vous surpasser?

Avant tout, ce fut le plus beau congrès auquel j’ai pu assister, et ce, pour plusieurs raisons.

1) je venais de divorcer et j’avais besoin de me changer les idées.

2) j’y suis allé avec mon meilleur ami depuis 1978, Howard Wall et j’adorais faire des petits concerts avec lui.

3) l’organisateur était la plus gentille des personnes, Joseph Hirschowitz. Il nous porta dans de beaux vignobles.

4) J'ai commandé mon premier cor Engelbert Schmid (que j'ai rencontré quelques années plus tard), car la réponse dans l'articulation me semblait mieux. J’allais acheter le modèle à compensation mais Howard m’a dit que j'avais un meilleur son sur le triple full Fa aigu, alors j’ai acheté ça. Aujourd’hui (13/06/2020), j’ai joué sur CE cor.

J’ai toujours fait plus confiance à mes amis qu’à moi-même, s’agissant d’acheter des cors et des embouchures.

En Allemagne, justement aux Journées du cor Schmid, (2018), nous enseignions toute la journée, mais à certaines heures, nous nous arrêtions sauf vous. Comment expliquez-vous ce besoin intérieur de partager votre savoir au point d’en oublier de vous arrêter.

Peur du devenir de la curiosité. Je n’ai jamais ressenti le fardeau d’étudier, parce que ce fut continuellement une quête pour satisfaire ma curiosité. Mes principaux domaines de curiosité:

-comment jouer du cor techniquement

-la structure du phrasé musical.

Si chaque étudiant montrait un intérêt pour la musique et surtout ces domaines spéciaux, intéressants pour moi, alors j’étais prêt à partager avec eux ce que je pensais avoir trouvé. Il n’y aucun étudiants qui ne soit curieux, pas seulement ces dernières années, je dirai: jamais. Quand vous les rencontrez, vous devez leur donner tout ce que vous avez en vous.

Si vous êtes curieux, vous n’avez pas besoin de discipline.

Pour parler d'auditions au New York Philharmonic, c'est bizarre pour nous de voir vos concours avec presque tous les tours sans accompagnement de piano. Je vous prie de nous expliquer pourquoi et si c'est fréquent en Amérique.

Oui c'est vrai, normalement on sollicite le piano seulement en finale. Je pense que la raison de ça est: les auditions servent à entendre si quelqu'un peut JOUER. Le stage dans l'orchestre (d'habitude de 17 mois) sert à savoir si l'élu peut ÉCOUTER. Le rôle du piano serait donc de voir si quelqu’un peut écouter mais nous n’avons pas trouvé cela probant jusqu'à présent. Par exemple, prenons le solo de 2ème au début de la 9ème de Mahler. À l'audition, on peut entendre comment un candidat va JOUER fort les sons bouchés, les pianissimos, les pianos, etc... Dans l'orchestre on va ensuite pouvoir se rendre compte comment quelqu'un ÉCOUTE ce qui il y a autour et engendre un dialogue avec cela.

Alors on entend

1) l’interruption du calme des 6 premières mesures de la première phrase avec les mesures forte bouchées.

2) accompagnement des violons (en syncopes) mesures 7 à 10

3) réponse au motif des violons (opposition) mesures 11 à 14

4) maintenant faire l'énoncé avec les violons répondant (opposés) mesures 15 à 17 (les choses se sont inversé)

En filant cela une fois dans une répétition d’orchestre, vous pouvez entendre si le nouveau deuxième cor sait, entend et répond à cet environnement. Je pense qu'avoir quelqu’un qui accompagne au piano à l’audition ne nous aide pas assez, quel que soit le degré d'interaction entre les deux.

La première fois que j'ai entendu le NY PHIL, c'était à Paris salle Pleyel sûrement dans les années 90 avec Zubin Mehta à la direction. Une belle 3ème de Schubert avec Jerome Ashby un peu fort au premier, puis le Sacre du Printemps joué incroyablement par vous (si fort et parfaitement propre, et ce, sans assistant) puis un bis de Duke Ellington arrangé pour orchestre symphonique, où Jerome avait encore quelques solos. Vous souvenez-vous de cette tournée?

30 ans après le départ de Zubin, nous jouions encore comme s'il dirigeait, sans s'occuper de qui était devant nous, tellement sa version était convaincante! Le passage dont je me souviens particulièrement était vers le grand chiffre 192. Il voulait les 3èmes et 4èmes mesures assez catégoriques. Puis les grands numéros suivants 193 à 196, cela devint une valse joyeuse et détendue. C'était idéal à jouer en le pensant en 3/4 même si le compte n'y est pas! Nous avons joué le Sacre si souvent avec lui, aussi bien que la cinquième de Mahler. La blague entre nous est que nous avons joué ces pièces en tournée car il ne nous servait même pas d'emporter les partitions. Les tournées en Europe étaient toujours plaisantes, car l'orchestre si était rendu si souvent que chacun savait l'endroit où il voulait retourner. Vous connaissiez les magasins, les hôtels, les restaurants (et en France le fromage). Il y avait pour nous un bond de qualité de vie, et les gens s'y sentaient si bien. D'autre part chacun connaissait déjà les acoustiques des salles de concert, ce qui simplifiait la vie.

La plupart des gens après une vie de labeur, pensent à ce qu’ils auraient pu faire différemment pour mieux réussir. Quand quelqu’un décroche la lune, de quoi peut-il encore rêver?

1) De la gratitude pour ce qu’on a reçu.

2) Je pense que toute personne âgée s’interroge sur le sens de la vie, quelle que soit sa profession. Il n’y a pas de réponse!

3) Une des plus belles pensées (non musicale) qui me soit venu était celle-ci : «Préfères-tu avoir raison ou être heureux?»

Je pense que nous voulons tous avoir raison, mais pour moi, cela a rarement conduit au bonheur.

Maintenant, j’essaie de me rendre heureux.

Coda: Comment voyez-vous Maître la musique classique dans notre société à l’horizon d’un demi-siècle?

Pour un mathématicien, 2+2=4 est un fait touchant. À cause de cela, il est devenu mathématicien. Pour moi, le cor demande une implication/signification physique et la structure de la musique (que je la respecte ou la combatte) a une implication émotionnelle.

Tant que les musiciens-interprètes ressentent ce sens émotionnel, ils seront capables de le communiquer au public et la musique classique perdurera.

Si nous arrivons à un stade où les artistes eux-mêmes perdent leur sensibilité émotionnelle en jouant la musique, alors nous aurons terminé, le classique ne survivra pas.

JUIN 2020

Inscrivez-vous au blog

Soyez prévenu par email des prochaines mises à jour

Rejoignez les 34 autres membres