HERMANN BAUMANN

HERMANN BAUMANN

IN ENGLISH, FRENCH AND PORTUGUESE SPEAKING

SEE DISCOGRAPHY BELOW

Maestro, you started the horn rather late, in what environment?

I come from Hamburg where I was born on August 1, in 1934. I grew up in the countryside, near the Elbe River, my two grandfathers were teachers, one taught me classical music. He played the organ for nearly 40 years and conducted choirs. And about my parents, my father was a doctor and my mother was a pianist. We loved to sing (still today!), my mother at the piano and around her we sang operas by Mozart and Lortzing. When I was 15, I started as a choir leader, and then when I was 16, I started my band as a drummer. When I was 17 I started playing the horn, nobody played it around me. I loved the sound so much that I put myself in the head to become a horn player. While student in Hamburg, I had my first engagement on the German TV. Live, I presented the horn and played Mozart "Komm lieber Mai, und mache die Baüme wieder grün" (Come dear Mai, and make the trees green again). During my studies I was solo horn of the chamber orchestra of Hamburg. We went by bus to Spain to make 20 concerts in 3 weeks. There was no water except from 20:00 till 22:00 hours. The wine cost was only 70 Pfennig per liter (almost nothing...) there was no shower... only wine!!

How from your studies at the Musikhochschule in Hamburg, did you become professional?

My teacher Fritz Huth from the Stadt Oper told me to try an orchestra audition at the age of 22 (after 5 years playing horn!) I went to Dortmund and I won the job.I wanted to know why I was taken, my future colleagues answered me: you are very young, well, let's see how long you stay in Dortmund... I stayed there 4 years, the morning rehearsal, the evening opera performance and the afternoon, personal practicing. I had only studied three semesters in Hamburg. I became solo horn in the middle of the 1956/57 season and the artistic director Rolf Agop quickly understood that I had to be engaged as soloist at least once. He put on R. Strauss’s 1st concerto. I played by heart as soloists do. I always played by heart, like my mother. After these 4 years, I went to the Stuttgart Radio and worked with wonderful conductors. The official music director was Hans Müller-Kray and as guest conductors came Karl Schuricht, Sergiu Celibidache, Karl Böhm, Benjamin Britten, Paul Hindemith, Helmut Rilling, Heinz Wallberg...

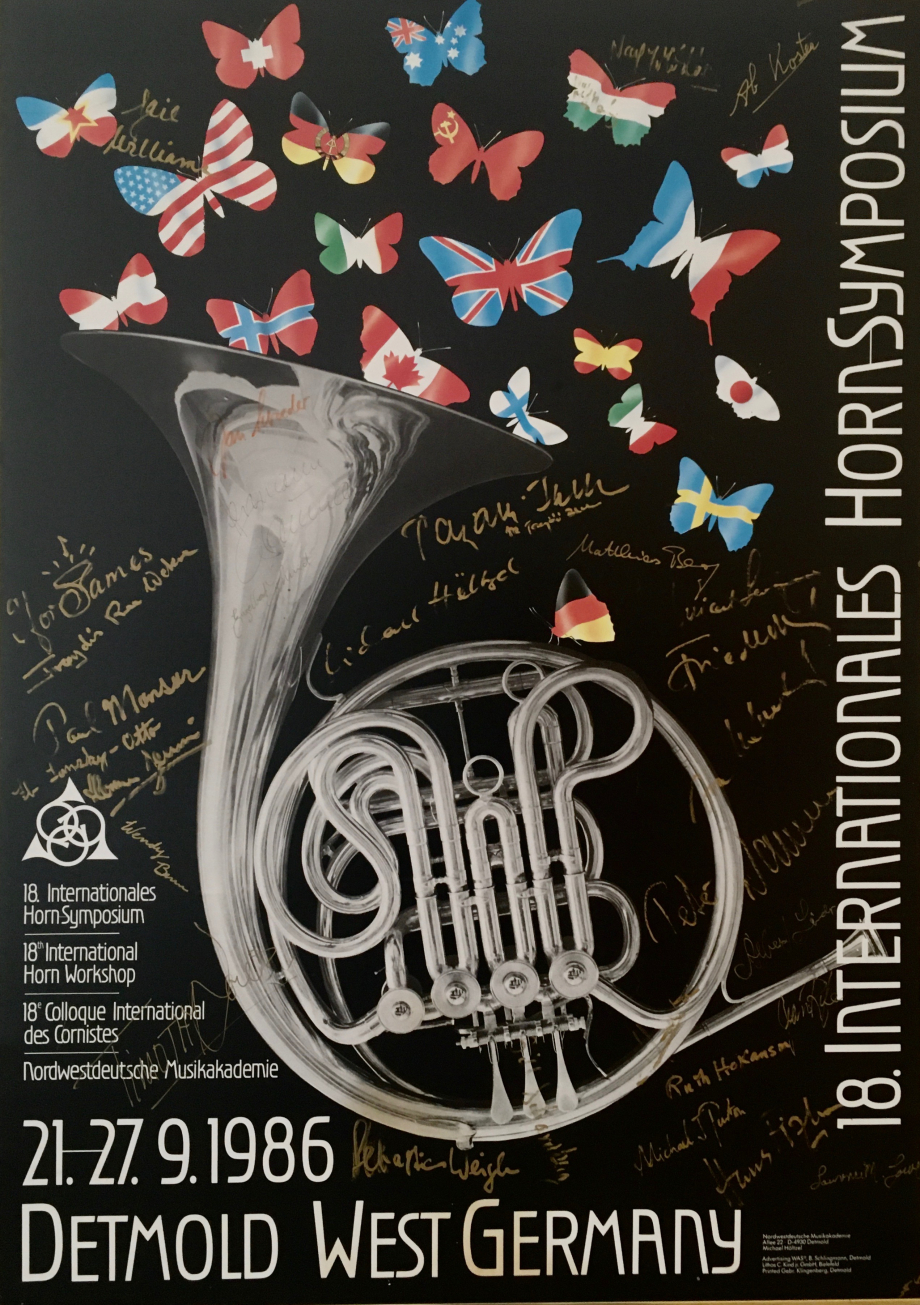

But did everything started after an International Competition?

In 1964 there was the ARD competition in Munich. I sent an application, my program was:

Beethoven Sonate

Mozart 3rd Cto

CM von Weber Concertino

R. Strauss 1st Cto

P. Hindemith Cto

Peter Racine Fricker Sonate

After 10 days of competition it was clear, I won the Munich ARD competition. Soprano Jessie Normann from the USA got a 2nd prize. The next contest she got first prize.

In an interview for the ARD, I said: I want to make the horn again a solo instrument.

Then I played on the TV Felix Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night's Dream. My eldest son who was 7 years old and was still on the Föhr Island in the North Sea (where I intensively prepared the competition) was allowed to watch TV longer on the evening of the TV interview. His daddy was on TV! The next day he quickly went to see his friend whose father was a baker and said to him: my father is the best horn player in the world!! And his friend replied: my father is the best baker in Föhr!!

Deutsche Welle Köln did a show with me that was then broadcast all over the world. The start of a global career. Journalist’s quote: when German horn player Hermann Baumann played the first bars of WA Mozart’s Cto n.3 for Horn and Orchestra, the musical world made a sensational discovery. Baumann not only won the first prize of his discipline but was also the real winner of the competition, because apart from him, no one else could have won a first prize. Conductor Dean Dixon, who was at the head of the Bayerische Rundfunk Orchester tonight, was also surprised by such a high quality sound, virtuosity and expression. Like the public who did not think that a horn player would be able to make this instrument sound so flawlessly, or even make it sing.

When I started playing the horn at 17, I immediately did it in a solo way, I played a lot of Franz Schubert lieds with my mother on the piano. I immediately played as a singer and this is my particular technique (which comes from the center of the body), the diaphragm as the basis of my playing. A lied by F. Schubert that I remember: "Am Brunnen vor dem Tore, da steht ein Lindenbaum" (At the fountain in front of the door there is a lime tree). Quote from a Deutsche Welle journalist: Baumann came to Munich not only as a mature artist but also with a very clear concept, a great deal of confidence in him.

After the first prize I had many solicitations, concerts in Innsbrück, the NDR in Hamburg, my orchestra in Stuttgart, in Baden Baden Radio, in Basel, in Paris at Radio France, in Lisbon in Portugal...

In the impossibility of holding an orchestra position in view of your engagements as a concertist, you have therefore thought of teaching, is that right?

The Folkwang Musik Hochschule in Essen wanted me as a teacher. There was an engagement in Rome as a soloist but I couldn’t go because I had Mahler’s sixth with Claudio Abbado and I didn’t get the week off. Abbado asked me why I was not in Berlin. "No way, I just resigned from Stuttgart to teach in Essen!"

Little anecdote: came La Callas, she had to sing for 17 min. On stage finally when the time came, there was an incredible tension, we played the ouverture we played again an ouverture... when she arrived there were very strong applause although she had not yet sung a single sound...

I never forgot that!

I started teaching in 1967, for 12 years. One day, I received a call from the WDR asking me to replace for a season in Köln, as the solo horn Erich Penzel was on sick leave. So I played at the Cologne Radio and taught in Essen. In one of the next concerts of this orchestra, a solo horn player was necessary...

Letting the critics speak after the concert, the title was: Baumanns Wunderhorn. It certainly does not happen often that a solo horn player flies to glory and puts in the dark a conductor like Sir John Barbiroli, but this was the case in the 6th concert of the Köln Radio. In this program, Hermann Baumann played the solo part of Benjamin Britten’s Serenade and it was beautiful. You have to be careful with superlatives but here they are in the right place. Perfection and virtuosity put everything away from what we knew until now.

What amazed everyone in your career, is the number of your recordings!

Twice a year I flew to West Berlin for recordings for RIAS and SFB and then followed up with recordings to Bremen, Hannover for WDR and HR. Then the Saarländischer Rundfunk, Kaiserslautern, Bayerische Rundfunk. I played at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam under the direction of Jaap Schröder, at the Chamber Orchestra of Karl Münchinger, in Vienna at the Consentus Musicus by Nicolaus Harnoncourt, followed by recordings.

Prior to your serious accident in 1993, did you experience periods of difficulty?

In Munich I was very well known but I had not yet played with Karl Richter. Maurice André, whom I had known for years, told Richter: you must hire Baumann from Stuttgart.

A tour in Italy and Switzerland in 1966 travelling by train was an experience for all of us. In Modena, we had a stage rehearsal before the concert and Richter says: the Aria of the Quoniam we have to play it complete tonight. I got up and played my part until the end and then I asked: do I have to change something?

Karl Richter laughed with the whole orchestra and the whole choir. And he said: that’s how I always imagined this air!

During this trip Karl Richter asked me: do you want to play with me at the Goldenersaal in Vienna?

... of course! (he wanted R. Strauss' 2nd Cto)

Wunderbar!

Karl Richter says: it will be with the Wiener Symphoniker in the cycle "the great symphonies".

It was a long winter, in early April, I went to the mountains to ski and sledge. We fell skiing, me and my daughter Johanna. She had nothing but I did. With pain we went to the nearest hospital. I broke a metacarpal bone in my hand, they had to cast. 18 days before the concert in Vienna! But I didn’t cancel. Alexander put a hook on the instrument so I could hold it better, lifting the weight thanks to a strap around my body. Day and night I was trying to free my fingers from plaster so that I could practice a little on my second R. Strauss Cto. I drove to Austria with my wife, still wearing a splint. We were in the Imperial Hotel, overlooking the Goldenersaal. Richter looked at me a little skeptical when he found out what had happened, the orchestra the same. The audience looked at me funny when coming on stage. This 2nd of Strauss being particularly difficult, at the end, the Viennese exalted with joy, delighted with such an interpretation in this mythical hall of Vienna.

Then the world opened up to me, my calendar was filling up more and more. My dear wife was not only a housewife with 4 children as often heard on TV, but was all day at the office and on the phone. Her Latin and German studies helped a little but then English and French took over.

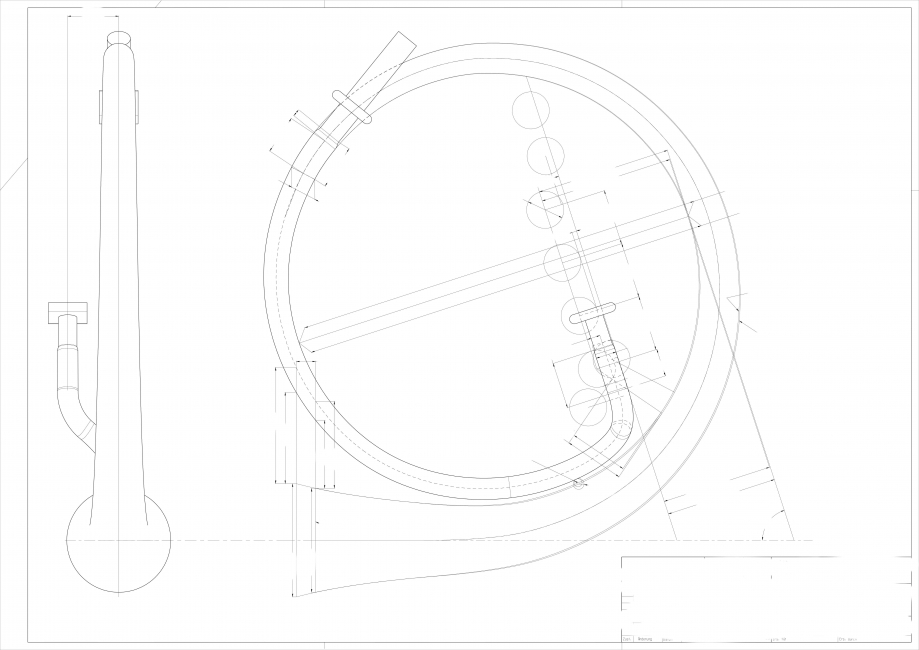

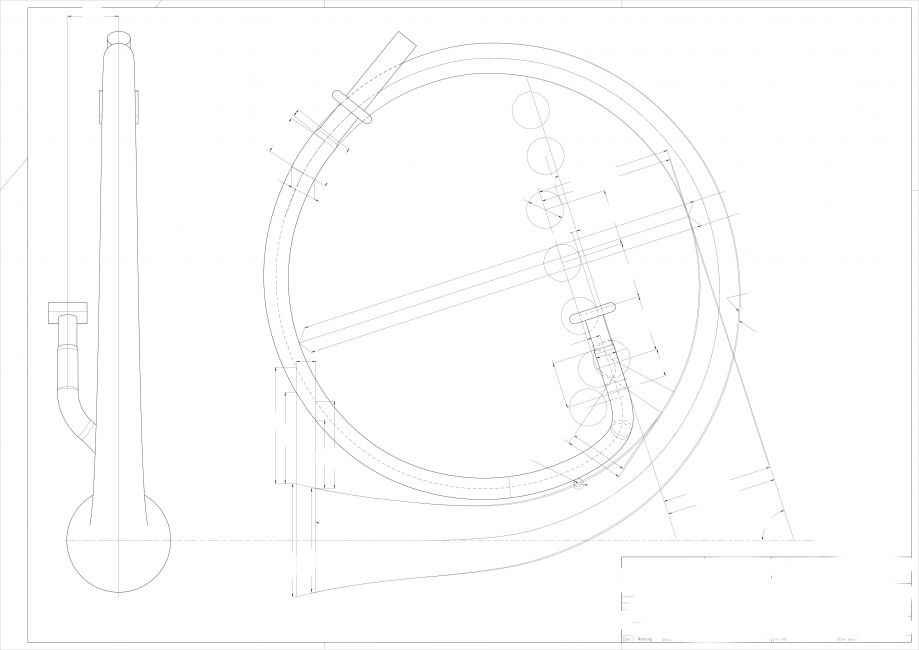

The natural horn, concerning you is also a beautiful love story...

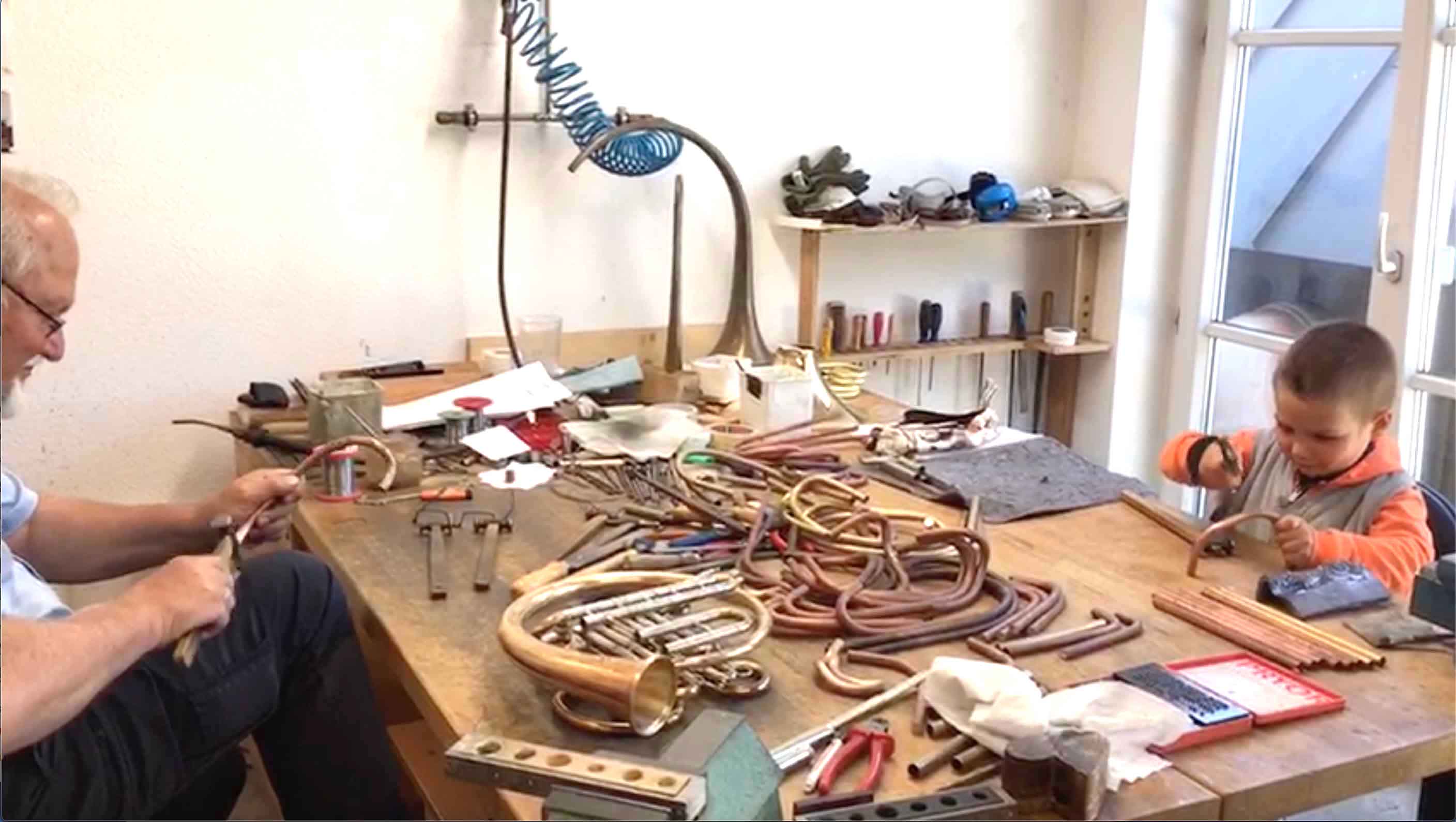

My students liked to meet to play together (orchestral excerpts) Bach, Beethoven, up to contemporary music. The music of the 18th and 19th centuries was played on natural horns. I started with playing it in 1967 and made available my own horns to my students. Subsequently the Musik Hochschule of Essen bought natural horns. The Folkwang Horn Ensemble did a lot of little concerts. The great mass of St Hubert made me particularly want to transcribe it. This piece is intended to be hunting and festive music. Movements offers caracters like festive, dignified, to cheerful, popular gathering… I did many concerts with this ensemble, the Mecca of the horn players. At the end of a concert with the great mass of St Hubert, 9 natural horns and 8 pistons horns shared the applause.

Every year I went to Vienna as a soloist, it lasted about twenty times. With Nicolaus Harnoncourt and the Consentus Musicus, we recorded the 4 concertos of WA Mozart, on the natural horn. In Oslo I was offered a Lure. In Copenhagen, Danish Queen Mutter Ingrid showed me a 300-year-old horns found in marshes. In 2005 in St Petersburg, I saw for the first time Russian horns of the 17th and 18th centuries. What is great is that you can only play one sound! Spontaneously I invited the Russian Horn Capella ensemble for concerts in Germany. In October 2006 I was the soloist and conductor and I also presented. In Italy, I often conducted and played the natural horn, for example in Florence, with a symphony by J. Haydn and then I played J.F. Handel, G.P. Telemann, J. Haydn or W.A. Mozart. We ended up with a beautiful symphony by W.A. Mozart.

After the horn concertos, the audience always wanted as encore my G. Rossini on natural horn and Mozart’s Horn signal on my Kelp.

I always enjoyed going to Milan with the Carme Ensemble, a superb little Chamber Orchestra. A tour took us to the south of France and then to Paris. After J. Haydn - W.A. Mozart, the highlight of the concert was the Trompe de France (French hunting trompes). From Paris we went straight to the USA. At Ann Arbour, there was the Gewandhaus Orchestra with Kurt Masur, Anne Sophie Mütter and me. Christoph von Dohnanyi brought me to Cleveland and then to Carnegie Hall in New York with the 3rd Cto by W.A. Mozart. This was my 33rd tour in the USA.

The expression "Go around the world" fits you perfectly!

They wanted to hear my Strauss 2nd everywhere: Warsaw, Krakow, Katovice, Oslo, Bergen, Trondheim, Helsinki, Tempere, Gothenburg, Stokkholm, Malmö, Reykjavik, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, Belgrad, Paris, Strasbourg, Lyon...

In almost all these cities, I gave masterclasses.

My dear Concertino by C.M. von Weber was filmed at Herrenchiemsee Castle by German TV for a show. Then there was the Sunday concert (Wie schön ist doch Musik!) very popular show, I played the 1st Cto of R. Strauss. Then there was in Munich the 3rd and 4th Cto of W.A. Mozart for the TV, then in Vienna 2 shows "horn and piano".

The Württembergische Kammerorchester accompanied me on a tour in South Africa (Cape Town, Pretoria, Johannesburg, Durban). I found on the beach a Kelp (African Horn) on which I played for years (including Mozart’s Horn Signal)

Our next tour took us to the Soviet Union, Moscow, St Petersburg, Riga. Handel, Haydn, Mozart.

Almost without break, we went to the United States.

At the "Mostly Mozart" Festival, I played the 3rd and 4th Ctos and then with the Tokyo String Quartet, the Kv. 407 quintet.

The Wiener Symphoniker hired me with the 1st Cto of R. Strauss for the Festwochen im Mai, then at the Salzburger Festspiele, I was asked for 2 concertos, one before the break and one after!

Thea Dispeker took me to represent America and Canada.

I went every 3 years to Japan, in all it was 10 tours of 3 weeks. With the orchestra of the NHK of Tokyo, the Konzerstück of R. Schumann directed by Heinz Wallberg. The concerts in Sapporo, Osaka, Kyoto and Tokyo were always filmed by television. The next trip was to Israel; for the Jerusalem Orchestra, I was the hero of the evening. With the chamber orchestra we went to Haifa and Tel Aviv. Then a tour with the Sandor Vegh Camerata in Paris and throughout France.

The strings of the Wiener Philharmoniker and the London Mozart Players accompanied me on tours in Germany.

Then 13 concerts with Weber Concertino in 14 days with the Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie Herford.

Then the 4th Cto of W.A. Mozart with the Munchener Philharmoniker in Zurich, Bale, Lucerne, Bern, Lausanne and Geneva. And again in New York where Thea Dispeker kissed my wife and me, so thrilled. Many concert organizers were impatient. Mostly Mozart again with the 4 concertos of W.A. Mozart.

Since 1964, I’ve played everything by heart, everything!

Then there were the encores: the last movement, the rondo, but this time on a horn without piston of Antoine Courtois 2 centuries old.

Then, from Rossini the great Fanfare in my own version for natural horn, including double and triple sounds.

Then my first of 3 trips to Australia. «Come blow your Horn, Hermann Baumann»

I was expected in Australia, me German, playing the horn like an Italian baritone. The press wrote: the ABC should try and catch this Horn blower again!

During the 2nd tour (Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Sydney, Hobart, and Perth) the organizers rented a Mississippi steamboat for my birthday party, with horn players coming with their family.

Everyone knows your recordings with Kurt Masur and Pinchas Zukerman, how did it happen?

In 1983, in Dubrovnik, Croatia, in the old town, I played with organ and who was in the audience? Maestro Kurt Masur with his son!

A few weeks later, I recorded in Leipzig R. Strauss and C.M. von Weber with the Gewandhausorchester.

A year later we did R. Glière, C. St Saëns, P. Dukas and E. Chabrier. When I returned to the USA with R. Glière in my luggage it became the new «tube» for big orchestra (with trombone, tuba and harp) 12 ctos of R. Glière on a trip. Sir Simon Rattle, already known on a concert in Copenhagen, toured with me in England with the 3rd Cto by W.A. Mozart and the 1st Cto by R. Strauss.

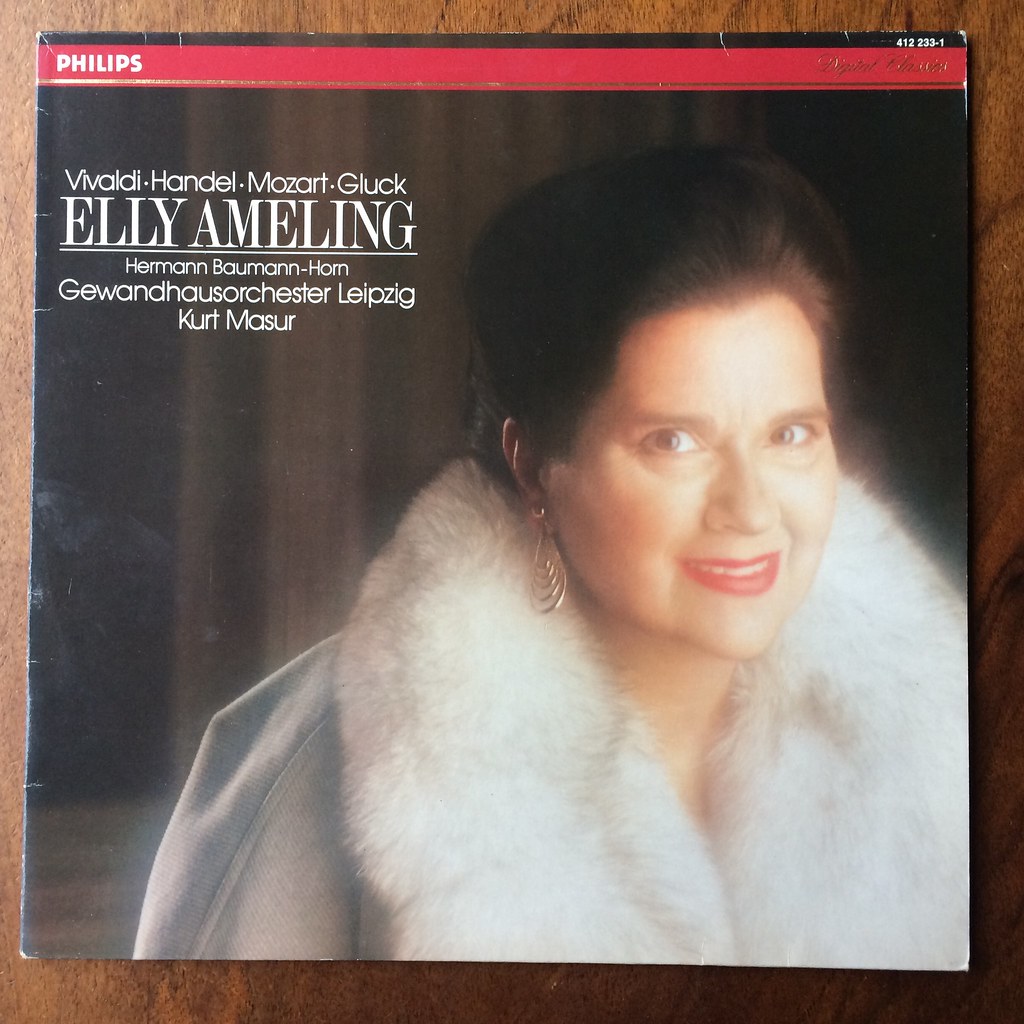

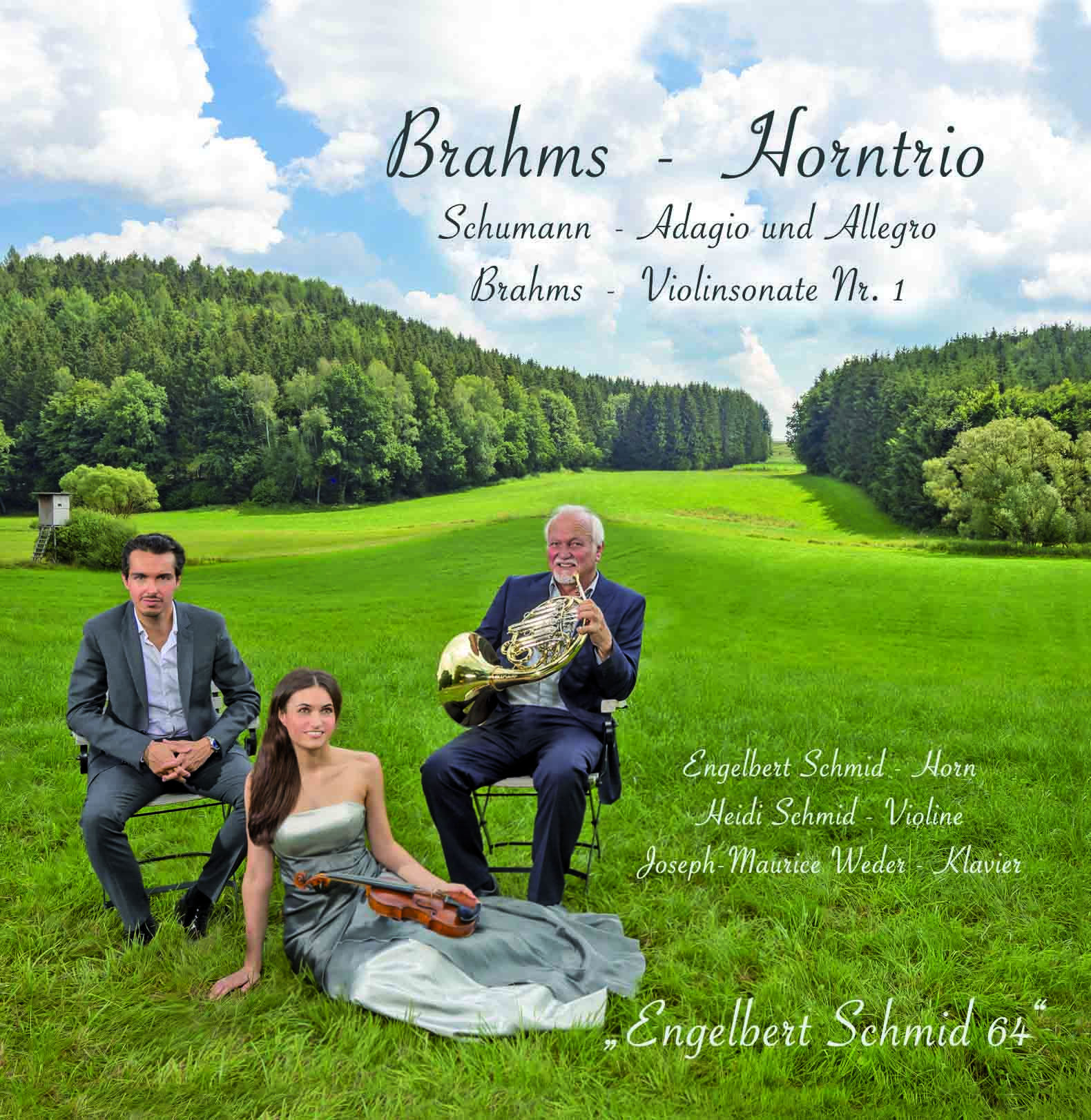

In New York with Pinchas Zukerman, I played the Brahms trio then with his St Paul Chamber Orchestra, I did a tour and the recording of Mozart’s 4 concertos for Philips. Then in London the recording with Academy St Martin in the Fields of J. Haydn’s and G.F. Telemann’s Ctos.

Your preferred partners?

Piano concerts are becoming more and more popular. Horn und Kavier

In America and Canada my pianist was Samuel Sanders who also played regularly with S. Rostropovich. In Europe it was Leonard Hokanson, Pi-Hsien Chen and Catherine Vickers.

Weird or incongruous things in your life?

A Masterclasse in Bern for horn players from all over the world was a fine example of what was expected of me: to make the horn shine as a soloist, to free it from a heaviness, and to give it the attractiveness of a solo instrument. In Bern and at the Gstaad-Saarnen of the Yehudi Menuhin Festival I played W.A. Mozart and Otmar Schoeck! In a discussion with J. Menuhin, he asked me if we could play the Brahms trio on the Alpine horn!

In Sydney I played on a Didgeridoo.

The Tubingen student orchestra and I received an invitation from Dresden in 1964. We went by bus to Dresden and we had a concert at the Dresdener Zwinger but there was no audience only those who followed us by chance...

We had our show on media silence. In the other part of the Zwinger we saw the light of the festivities of the 15 years of the DDR!

Please tell us the circumstances of your terrible accident.

In 1993, the evening of January 9th was typical of my life, I played R. Strauss' 2nd Cto with the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra. The concert was good I had good reviews. After the concert I was invited to dinner, then the next day I had to go back to Dusseldorf. In the night I had a stroke (apoplexy). I could no longer walk or talk. It is even difficult today. Only after years, I was able to play again; a long time during which I struggled. But there are people who believe in you. Thea Dispecker told me: You have to come back on stage. The first concerts were not so beautiful, but in progress. I thought of José Carreras with whom I had made a concert in Lucerne in 1990, and José overcame leukemia. It gave me strength.

Since then, I have given concerts in many countries: Switzerland, Turkey, Spain, Italy, Bulgaria, Israel, Japan, Korea, America, Brazil, Argentina, Alaska, Canada, Iceland, Russia, Serbia, Czech Republic, Croatia, Belgium, France, Portugal, Austria, Greece, China, Finland…

Maestro, do you have any closing remarks?

Here is a passage from my biography written by my wife Hella, who died 2 years after my accident: He plays the horn as expresses a great singer. It is not the technique alone that makes the art of Hermann Baumann, but its ability to assume different roles: the horn certainly has a wide variety of characters, colors and atmospheres. A brassy and decisive attack, a heroic pathos, the dramatic singing, the idyll of a lied, a melancholic past, the serious festive Sarrastro, but also the delectable irony of Till Eulenspiegel.

The New York Times once wrote: a horn player like him is born if you get lucky once a century.

JULY 2020

Maestro, vous avez commencé le cor plutôt tard, dans quel environnement?

Je viens de Hambourg où je suis né le 1er Août 1934. J'ai grandi à la campagne, proche du fleuve Elbe, mes 2 grands-pères étaient professeurs, l'un m'a enseigné la musique. Il a joué de l'orgue pendant près de 40 ans et a dirigé des choeurs. Quand à mes parents, mon père était médecin et ma mère pianiste. Nous aimions chanter (toujours aujourd'hui!), ma mère au piano et autour d'elle on chantait des opéras de Mozart et de Lortzing. À 15 ans j’ai débuté comme chef de choeur d’hommes, puis à 16 ans j’ai fondé mon groupe comme batteur. À 17 ans j’ai commencé le cor, personne n’en jouait autour de moi. J’ai tellement aimé le son que je me suis mis dans la tête de devenir corniste. Alors étudiant à Hambourg, j’ai eu mon 1er engagement à la tv allemande. En direct, j’ai présenté le cor et joué de Mozart "Komm lieber Mai, und mache die Baüme wieder grün" (Viens cher Mai, et refais verdir les arbres)

Pendant mes études j’ai été cor solo de l’orchestre de chambre de Hambourg. Nous sommes allés en bus en Espagne pour faire 20 concerts en 3 semaines. Il n’y avait pas d’eau sauf de 20 a 22 heures. Le vin ne coutait que 70 Pfennig par litre (3 fois rien...) il n’y avait pas de douche... seulement du vin!!!

Comment de vos études à la Musikhochschule de Hambourg, êtes-vous devenu professionnel?

Mon professeur Fritz Huth de la Stadt Oper m’a dit d’essayer un concours d’orchestre à l’âge de 22 ans (après 5 ans de cor!) je suis allé à Dortmund et ai gagné le concours. J'ai voulu savoir pourquoi on m’avait pris, mes futurs collègues m'ont répondu: tu es très jeune, on verra bien jusqu’à quand tu resteras à Dortmund... J'y suis resté 4 ans, le matin répétition, le soir représentation d'opéra et l’après-midi, travail personnel. J’avais seulement étudié 3 semestres à Hambourg.

Je suis devenu cor solo au milieu de la saison 1956/57 et le directeur artistique Rolf Agop a vite compris qu’il fallait m’engager en tant que soliste au moins une fois. Il a mis au programme le 1er de R. Strauss. J’ai joué par coeur comme le font les solistes. J’ai toujours tout joué par coeur, comme ma mère. Après ces 4 années, je suis allé à la Radio de Stuttgart et ai travaillé avec de merveilleux chefs. Le directeur musical attitré était Hans Müller-Kray et comme chefs invités venaient Karl Schuricht, Sergiu Celibidache, Karl Böhm, Benjamin Britten, Paul Hindemith, Helmut Rilling, Heinz Wallberg...

Mais tout a-t-il "décollé" suite au concours d'interprétation?

En 1964 il y avait le concours de l'ARD de Munich. J’ai envoyé une candidature, mon programme était:

Beethoven Sonate

Mozart 3ème Cto

CM von Weber Concertino

R. Strauss 1er Cto

P. Hindemith Cto

Peter Racine Fricker Sonate

Après 10 jours de compétition c’était clair, j’avais gagné le concours de Munich. La soprano Jessie Normann des USA a eu un 2eme prix. Le concours suivant elle a eu le 1er prix.

Dans une interview pour l'ARD, j’ai dit: je veux de nouveau rendre le cor un instrument soliste . Ensuite j’ai joué pour le public de la télévision le Nocturne du Songe d’une Nuit d'Été de Félix Mendelssohn. Mon fils ainé qui avait 7 ans et qui était encore sur l’ile Föhr en mer du nord, (où je me suis préparé de façon intensive au concours) a eu le droit de regarder la tv plus longtemps le soir de l’interview télévisée. Son papa était à la tv! Le jour d’après il est allé vite voir son copain dont le père était boulanger et lui dit: mon père est le meilleur corniste du monde!!! Et son copain répondit: mon père est le meilleur boulanger de Föhr!!!

La Deutsche Welle Köln a fait une émission avec moi qui a été retransmise ensuite dans le monde entier. Le début d’une carrière mondiale. Citation d'un journaliste: quand le corniste allemand Hermann Baumann a joué les 1ères mesures du Cto n.3 de WA Mozart pour Cor et orchestre, le monde musical a fait une découverte sensationnelle. Baumann n’a pas seulement bien mérité le 1er prix de sa discipline mais fut même le vrai vainqueur du concours, car à part lui, personne d'autre n’a pu avoir un premier prix. Le chef d’orchestre Dean Dixon qui était à la tête ce soir du Bayerische Rundfunk Orchester fut également surpris d'une telle qualité de son, virtuosité et expression. Comme le public qui ne pensait pas qu’un corniste serait capable de faire sonner de façon aussi impeccable cet instrument, voire de le faire chanter.

Quand j’ai commencé à jouer du cor à 17 ans, je l’ai tout de suite fait d’une façon soliste, j’ai joué beaucoup de lieds de Franz Schubert avec ma mère au piano. J’ai tout de suite joué comme un chanteur et c’est cela ma technique particulière (qui vient du centre du corps), le diaphragme comme base de mon jeu. Un lied de F. Schubert dont je me souviens: "Am Brunnen vor dem Tore, da steht ein Lindenbaum" (À la fontaine devant la porte il y a un tilleul). Citation d’un journaliste du Deutsche Welle: Baumann venait à Munich pas seulement comme artiste mature mais aussi avec un concept très clair, une grande portion de confiance en lui.

Apres le 1er prix j’ai eu bcp de solicitations, des concerts à Innsbrück, au N.D.R. de Hambourg, avec mon orchestre à Stuttgart, à la Radio de Baden Baden, Bâle, Paris à Radio France, à Lisbonne au Portugal...

Dans l'impossibilité de tenir un poste d'orchestre au vu de vos engagements comme concertiste, vous avez donc pensé à l'enseignement, c'est bien cela?

La Folkwang Musik Hochschule de Essen voulait m’avoir comme professeur. Il y avait un engagement à Rome en soliste mais je n’ai pas pu y aller car j’avais la sixième de Mahler avec Claudio Abbado et je n'ai pas eu le permis. Abbado m’a demandé pourquoi je n’étais pas à Berlin. Pas question, je viens de démissionner de Stuttgart pour enseigner à Essen!

Petite anecdote: chez nous venait La Callas, elle devait chanter pendant 17 min. Sur scène enfin le moment venu, il y avait une tension incroyable, on a joué l’ouverture on a rejoué une ouverture... quand elle est arrivée il y a eu des applaudissements très forts bien quelle n’avait pas encore chanté une note... j’ai jamais oublié cela!

J’ai commencé ainsi à enseigné en 1967, et ce pendant 12 ans. Un jour, j’ai reçu un appel du W.D.R. me demandant de remplacer pendant une saison à Köln, car le Cor solo Erich Penzel était en arrêt maladie. Du coup j’ai joué à la Radio de Cologne et enseigné à Essen. Dans un des prochains concerts de cet orchestre, il fallait un corniste soliste...

Laissant parler la critique après le concert, le titre fut: Baumanns Wunderhorn. Il arrive certainement pas souvent qu’un corniste soliste vole vers la gloire et met dans la pénombre un chef d’orchestre comme Sir John Barbiroli, mais c’était le cas dans le 6ème concert de la radio de Köln. Dans ce programme, Hermann Baumann jouait la partie soliste de la Sérénade de Benjamin Britten et c’était magnifique. Il faut faire attention avec les superlatifs mais ici, ils sont à la bonne place. La perfection et la virtuosité a mis tout à l’écart de ce que l’on connaissait jusqu’à maintenant.

Ce qui frappe notamment au regard de votre carrière, c'est le nombre d'enregistrements!

2 fois par an je volais à Berlin Ouest pour des enregistrements pour le RIAS et le SFB et ensuite ont suivi des enregistrements à Bremen, Hannover pour le WDR et le HR. Ensuite le Saarländischer Rundfunk, Kaiserslautern, Bayerische Rundfunk. J’ai joué au Concertgebouw d'Amsterdam sous la direction de Jaap Schröder, à l’Orchestre de Chambre de Karl Münchinger, à Vienne au Consentus Musicus de Nicolaus Harnoncourt, s'en sont suivis des enregistrements.

Avant votre grave accident de 1993, avez-vous connu des périodes de difficultés?

À Munich j’ai été très connu mais je n'avais pas encore joué avec Karl Richter. Maurice André, que je connaissais depuis des années a dit a Richter: il faut que tu engages Baumann de Stuttgart.

Une tournée Italie et Suisse en 1966 avec le train fut une expérience pour nous tous. A Modène, on a eu un raccord avant le concert et Richter dit: l’Aria du Quoniam on doit le jouer en entier ce soir. Je me suis levé et ai joué mon air jusqu’à la fin ensuite j’ai demandé: est-ce que je dois changer quelque chose?

Karl Richter a explosé de rire avec tout l’orchestre ainsi que tout le choeur. Karl Richter a dit: c’est comme cela que je me suis toujours imaginé cet air!

Pendant ce voyage Karl Richter m’a demandé: est-ce que vous voulez jouer avec moi au Goldenersaal de Vienne? ... bien sûr! (il voulait le 2ème Cto de R. Strauss)

Wunderbar!

Karl Richter dit: ce sera avec les Wiener Symphoniker dans le cycle "les grandes symphonies".

C’était un long hiver début avril, je suis allé à la montagne pour skier et faire de la luge. On est tombé en ski, moi et ma fille Johanna. Elle n’a rien eu mais moi si. Avec des douleurs on est allé à l'hôpital le plus proche. Je me suis cassé un os métacarpien de la main, ils ont dû plâtrer. 18 jours avant le concert à Vienne! Mais je n’ai pas annulé. Alexander m'a mis un crochet sur l’instrument pour que je puisse le tenir mieux, délestant le poids grâce à une sangle autour de mon corps. Jour et nuit j’essayais de libérer mes doigts du plâtre pour pouvoir travailler un peu mon second Cto de R. Strauss au niveau des doigtés. Je suis allé en voiture en Autriche avec ma femme, portant toujours une attelle. On était dans l’hôtel Impérial, avec vue sur le Goldenersaal. Richter me regarda un peu sceptique quand il a su ce qu’il s’était passé, l’orchestre pareil. Le public m’a regardé bizarrement à la vue de mon attirail.

Ce 2ème de Strauss étant particulièrement difficile, à la fin, les Viennois ont exalté de joie, ravis d’une telle interprétation dans le cette mythique salle de Vienne.

Puis le monde s’ouvrit à moi, mon agenda se remplissait de plus en plus. Ma chère femme n’était pas seulement femme d’intérieur avec 4 enfants comme souvent entendu à la télé, mais était toute la journée au bureau et au téléphone. Ses études de latin et allemand ont un peu aidé mais ensuite l’anglais et le français ont pris le dessus.

Le cor naturel, vous concernant c'est aussi une belle histoire d'amour...

Mes élèves se rencontraient pour jouer ensemble (traits d’orchestres) Bach Beethoven, jusqu’à la musique contemporaine. La musique des 18ème et 19ème siècles était jouée sur des cors naturels. J’ai commencé le jeu du cor simple en 1967 et mis à disposition mes propres cors à mes élèves. Par la suite la Musik Hochschule de Essen a acheté des cors naturels. Le Folkwang Horn Ensemble a fait beaucoup de petits concerts. La grande messe de St Hubert m’a donné particulièrement envie de la transcrire. Cette pièce a vocation d’être une musique de chasse et de fête. Les mouvements vont de festif, dignité, jusqu’à gaité, rassemblement populaire… J’ai fait de nombreux concerts avec cet ensemble, la Mecque des cornistes. À la fin d’un concert avec la grande messe de St Hubert, ce sont 9 cors naturels et 8 cors à pistons qui se sont partagés les applaudissements.

Chaque année j’allais a Vienne en soliste, cela a duré une vingtaine de fois. Avec Nicolaus Harnoncourt et le Consentus Musicus, nous avons enregistré les 4 concertos de WA Mozart, sur cor naturel. A Oslo on m’a offert un Lure. A Copenhagen, la reine Danoise Mutter Ingrid m’a montré des cors (cornes) vieux de 300 ans trouvés dans des marais. En 2005 à St Petersbourg, j’ai vu pour la première fois des cors russes des 17eme et 18eme siècles. Ce qui est génial c’est qu’on ne peut jouer qu’un seul son! Spontanément j’ai invité le Russian Horn Capella pour des concerts en Allemagne. En octobre 2006 j’étais le soliste et chef puis je présentais également. En Italie, j’ai souvent dirigé puis joué le cor naturel, par exemple à Florence, avec une symphonie de J. Haydn puis je jouais J.F. Haendel, G.P. Telemann, J. Haydn ou W.A. Mozart. On finissait avec une belle symphonie de W.A. Mozart.

Après les concertos pour cor, le public a toujours voulu comme bis mon G. Rossini sur cor naturel et le Horn signal de Mozart sur mon Kelp.

J’ai toujours aimé aller a Milan avec le Carme Ensemble, un superbe petit Orchestre de Chambre. Une tournée nous a mené dans le sud de la France puis à Paris. Apres nos J. Haydn - W.A. Mozart, le point fort du concert était la Trompe de France (les trompes de chasse françaises). De paris on a enchainé avec les USA. À Ann Arbour, il y avait l'Orchestre du Gewandhaus avec Kurt Masur, Anne Sophie Mütter et moi. Christoph von Dohnanyi m’a fait venir a Cleveland puis au Carnegie Hall de New-York avec le 3ème Cto de W.A. Mozart. Ce fut ma 33eme tournée aux USA.

L'expression "Faire le tour du monde" vous colle à merveille!

On a voulu entendre mon 2ème de R. Strauss partout: Varsovie, Cracovie, Katovice, Oslo, Bergen, Trondheim, Helsinki, Tempere, Göteborg, Stokkholm, Malmö, Reykjavik, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, La Haye, Belgrad, Paris, Strasbourg, Lyon...

Dans presque toutes ces villes, j’ai donné des masterclasses.

Mon cher Concertino de C.M. von Weber fut filmé au château Herrenchiemsee par la tv allemande pour une émission. Ensuite il y eu le concert du Dimanche (Wie schön ist doch Musik!) émission très populaire, j’y ai joué le 1er Cto de R. Strauss. Ensuite il y a eu a Munich les 3ème et 4ème Cto de W.A. Mozart pour la tv puis à Vienne 2 émissions "cor et piano".

Le Württembergische Kammerorchester m’a accompagné dans une tournée en Afrique du Sud (Le Cap, Pretoria, Johannesburg, Durban). J’y ai trouvé sur la plage un Kelp (Corne Africaine) sur laquelle j’ai joué pendant des années (notamment le Horn signal de Mozart)

Notre tournée suivante nous a emmené en Union Soviétique, Moscou, St Petersbourg, Riga. Haendel, Haydn, Mozart.

Quasiment sans pause, mous avons enchainé pour les Etats-Unis.

Au Festival "Mostly Mozart", j’ai joué les 3ème et 4ème Ctos puis avec le Quatuor à cordes de Tokyo, le quintette Kv. 407.

Les Wiener Symphoniker m’ont engagé avec le 1er Cto de R. Strauss pour les Festwochen im Mai, puis au Salzburger Festspiele, on m’a demandé 2 concertos, un avant la pause et l’autre après!

Thea Dispeker m’a pris en représentation pour l’Amérique et le Canada.

Je suis allé tous les 3 ans au Japon, en tout ce fut 10 tournées de 3 semaines. Avec l’orchestre de la NHK de Tokyo, le Konzerstück de R. Schumann dirigé par Heinz Wallberg. Les concerts à Sapporo, Osaka, Kyoto et Tokyo étaient toujours filmés par la télévision. Le voyage suivant allait en Israël; pour le Jerusalem Orchestra, j’ai été le héros de la soirée. Avec le chamber orchestra on est allé a Haifa et Tel Aviv.

Puis une tournée avec le Sandor Vegh Camerata à Paris et dans toute la France.

Les cordes du Wiener Philharmoniker et du London Mozart Players m’ont accompagné dans des tournées en Allemagne.

Puis 13 concerts avec le cto de Weber en 14 jours avec le Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie Herford.

Ensuite le 4ème Cto de W.A. Mozart avec les Munchener Philharmoniker à Zurich, Bale, Lucerne, Bern, Lausanne et Genève. Et de nouveau a New York où Thea Dispeker nous a embrassé ma femme et moi, si ravie. Beaucoup d’organisateurs de concerts furent impatients. Mostly Mozart encore avec les 4 concertos de W.A. Mozart.

Depuis 1964, j’ai tout joué par coeur, tout!

Puis il y a eu des bis: le dernier mouvement, le rondo, mais cette fois-ci sur un cor sans piston d’Antoine Courtois vieux de 2 siècles.

Ensuite, de Rossini la grande fanfare dans ma propre version pour cor naturel, incluant des sons doubles et triples dans la cadence.

Ensuite mon premier de 3 voyages en Australie. « Come blow your Horn, Hermann Baumann »

J’étais attendu en Australie, moi l’allemand, jouant du cor comme un baryton italien. La presse a écrit: the ABC should try and catch this Horn blower again!

Pendant la 2ème tournée (Adélaïde, Brisbane, Melbourne, Sydney, Hobart, et Perth) les organisateurs ont loué un bateau a vapeur type Mississipi pour ma fête d’anniversaire, avec des cornistes venus en famille.

Tout le monde connaît vos enregistrements avec Kurt Masur et Pinchas Zukerman, comment c'est arrivé?

En 1983, à Dubrovnik en Croatie, dans la vieille ville, j’ai joué avec orgue et qui était dans le public? Le maestro Kurt Masur avec son fils!

Quelques semaines plus tard, j’enregistrais à Leipzig R. Strauss et C.M. von Weber avec le Gewandhausorchester.

Un an plus tard on a fait R. Glière, C. St Saëns, P. Dukas et E. Chabrier. Quand je suis retourné aux USA avec R. Glière dans mes bagages c’est devenu le nouveau « tube » pour grand orchestre (avec trombone, tuba et harpe) 12 ctos de R. Glière sur un voyage. Sir Simon Rattle déjà connu sur un concert à Copenhague, a fait avec moi une tournée en Angleterre avec le 3ème Cto de W.A. Mozart et le 1er Cto de R. Strauss.

À New-York avec Pinchas Zukerman, j’ai joué le trio de Brahms ensuite avec son St Paul Chamber Orchestra, j’ai fait une tournée et l’enregistrement des 4 concertos de Mozart pour Philips. Puis à Londres l'enregistrement avec Academy St Martin in the Fields des Ctos de J. Haydn et G.F. Telemann.

Vos partenaires privilégiés?

Les concerts avec piano deviennent de plus en plus populaires. Horn und Kavier

En Amérique et Canada mon pianiste était Samuel Sanders qui jouait aussi régulièrement avec M. Rostropovich. En Europe c’était Leonard Hokanson, Pi-Hsien Chen et Catherine Vickers.

Des choses bizarres ou incongrues dans votre vie?

Une Masterclasse à Bern pour des cornistes du monde entier était un bel exemple de ce qu’on attendait de moi: faire briller le cor en tant que soliste, le libérer d’une lourdeur, et lui donner l’attractivité d’un instrument soliste. À Bern et au Gstaad-Saarnen du Yehudi Menuhin Festival j’ai joué W.A. Mozart et Otmar Schoeck! Dans une discussion avec J. Menuhin, il m’a demandé si on pouvait jouer le trio de Brahms sur le cor des Alpes! À Sydney j’ai joué sur un Didgeridoo.

L’orchestre des étudiants de Tubingen et moi avons recu une invitation de Dresden en 1964. On est allé en bus a Dresde et nous avons eu un concert au Dresdener Zwinger mais il n’y avait pas de public seulement ceux qui nous ont suivi par hasard...

On a passé notre concert sous silence médiatiquement parlant. Dans l’autre partie du Zwinger nous avons vu la lumière des festivités des 15 années des DDR!

Racontez-nous s'il-vous plaît les circonstances de votre terrible accident.

En 1993, la soirée du 9 janvier était typique de ma vie, j’ai joué le 2ème Cto de R. Strauss avec le Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra. Le concert était bien j’en ai eu de bonnes critiques. Après le concert j’étais invité a diner, puis le lendemain je devais retourner a Dusseldorf. Dans la nuit j’ai eu un accident vasculaire cérébral (apoplexie). Je ne pouvais plus marcher ou parler. C’est même difficile encore aujourd’hui. Seulement après des années, j’ai pu rejouer; une longue période pendant laquelle j’ai lutté. Mais il y a des gens qui croient en toi. Thea Dispecker m’a dit: Il faut que tu reviennes sur scène. Les premiers concerts n’étaient pas si beaux, mais en voie de progrès. J’ai pensé à José Carreras avec lequel j’avais fait un concert à Lucerne en 1990, et José a surmonté la leucémie. Cela m’a donné la force.

Depuis, j’ai redonné des concerts dans plein de pays: Suisse, Turquie, Espagne, Italie, Bulgarie, Israël, Japon, Corée, Amérique, Brésil, Argentine, Alaska, Canada, Islande, Russie, Serbie, République Tchèque, Croatie, Belgique, France, Portugal, Autriche, Grèce, Chine, Finlande…

Maestro, auriez-vous un mot pour conclure?

Voici un passage de ma biographie écrit par ma femme Hella, décédée 2 ans après mon accident: Il joue du cor comme s'exprime un grand chanteur. Ce n’est pas la technique seule qui fait l’art d'Hermann Baumann, mais sa capacité à endosser différents rôles: le cor a certainement une grande variété de caractères, couleurs et atmosphères. Une attaque cuivrée et décisive, un pathos héroïque, le chant dramatique, l’idylle d’un lied, un passé mélancolique, le sérieux festif de Sarrastro, mais aussi l’ironie délurée de Till Eulenspiegel.

Le New-York Times a un jour écrit: un corniste comme lui naît si on a la chance une fois par siècle.

JUILLET 2020

remerciements à P. Lagrange

Mestre, começou a tocar trompa bastante tarde, em que ambiente?

Sou de Hamburgo, onde nasci a 1 de agosto de 1934. Cresci no campo, perto do rio Elba, ambos os meus dois avôs eram professores, um ensinou-me música clássica. Tocou órgão durante quase 40 anos e dirigia coros. E sobre meus pais, o meu pai era médico e a minha mãe era pianista. Adorávamos cantar (ainda hoje adoro!), a minha mãe ficava ao piano e ao seu redor cantávamos óperas de Mozart e Lortzing. Quando eu tinha 15 anos, comecei como líder de coro e, aos 16, comecei numa banda como baterista. Quando tinha 17 anos, comecei a tocar trompa, ninguém ao meu redor tocava o instrumento. Amei tanto o som que coloquei na minha cabeça que me iria tornar trompista.

Enquanto estudante em Hamburgo, tive a minha primeira aparição na TV alemã. Ao vivo, apresentei a trompa e toquei Mozart "Komm lieber Mai, und mache die Baüme wieder grün" (Vem querido Maio, e torna as árvores verdes novamente). Durante os meus estudos, fui trompa solista da orquestra de câmara de Hamburgo.

Fomos de autocarro a Espanha para fazer 20 concertos em 3 semanas. Não havia água, exceto das 20:00 às 22:00 horas. O custo do vinho foi de apenas 70 Pfennig por litro (quase nada ...) não havia chuveiro ... apenas vinho !!

Com os seus estudos na Musikhochschule em Hamburgo tornar-se-ia profissional, como foi?

Meu professor Fritz Huth, da Stadt Oper, disse-me para fazer eu tentar uma audição orquestral, com 22 anos de idade (depois de 5 anos a tocar trompa!). Fui para Dortmund e ganhei o lugar. Eu queria saber porque fui escolhido, os meus futuros colegas responderam-me: você é muito jovem, bem, vamos ver quanto tempo vai ficar em Dortmund ... Eu fiquei lá 4 anos, ensaio matinal, récita de ópera à noite e de tarde estudo individual. Eu tinha somente estudado três semestres em Hamburgo. Tornei-me trompa solista a meio da temporada de 1956/57 e o diretor artístico Rolf Agop cedo entendeu que eu tinha que ser convidado para solista pelo menos uma vez. Ele colocou o 1º Concerto de R. Strauss. Toquei-o de memória como faz um solista. Eu sempre toquei de memória, como minha mãe. Após esses 4 anos, fui para a Rádio de Estugarda e trabalhei com maestros maravilhosos. O diretor musical oficial era Hans Müller-Kray e como maestros convidados tivemos Karl Schuricht, Sergiu Celibidache, Karl Böhm, Benjamin Britten, Paul Hindemith, Helmut Rilling, Heinz Wallberg ...

Mas tudo começou depois de um Concurso Internacional?

Em 1964, houve o Concurso ARD em Munique. Eu enviei uma inscrição, o meu programa era:

Sonata de Beethoven

3º Concerto de Mozart

Concertino de CM von Weber

1º Concerto de Richard Strauss

Concerto de P. Hindemith

Sonata de Peter Racine Fricker

Após 10 dias de concurso estava claro, venci o Concurso ARD de Munique. A soprano Jessie Normann, dos EUA, recebeu o 2º prémio. No concurso seguinte, ela conquistou o primeiro prémio.

Numa entrevista para a ARD, eu disse: Eu quero tornar a trompa novamente num instrumento solista.

Depois, toquei na TV ‘Sonho de Uma Noite de Verão’ de Felix Mendelssohn. O meu filho mais velho, que tinha 7 anos e ainda estava na ilha de Föhr, no Mar do Norte (onde eu preparei intensamente o concurso), foi autorizado a assistir televisão mais tempo na noite da entrevista na TV. O seu pai estava na TV! No dia seguinte, ele procurou ver o seu amigo, cujo pai era padeiro, e disse-lhe: o meu pai é o melhor trompista do mundo!! E seu amigo respondeu: o meu pai é o melhor padeiro de Föhr !!

A Deutsche Welle Köln fez um programa comigo que foi transmitido para todo o mundo. O início de uma carreira global. Citação do jornalista: quando o trompista alemão Hermann Baumann tocou os primeiros compassos do Concerto n.3 de WA Mozart para Trompa e Orquestra, o mundo musical fez uma descoberta sensacional. Baumann não só ganhou o primeiro prémio na sua disciplina, mas foi também o verdadeiro vencedor do concurso, porque para além dele, ninguém mais poderia ganhar o primeiro prémio. O maestro Dean Dixon, que estava à frente do Bayerische Rundfunk Orchester essa noite, também ficou surpreso com um som de tamanha qualidade, virtuosidade e expressividade. Tal como o público, que achava que um trompista não seria capaz de fazer este instrumento soar tão perfeito, ou até mesmo fazê-lo cantar.

Quando comecei a tocar trompa aos 17 anos, imediatamente o fiz de uma forma solista, toquei muitos Lieder de Franz Schubert com a minha mãe no piano. Eu de imediato toquei como um cantor e essa é a minha técnica particular (que vem de dentro do corpo), o diafragma como base da minha execução. Um Lied de F. Schubert que eu me recordo: "Am Brunnen vor dem Tore, da steht ein Lindenbaum" (Na fonte em frente à porta há uma tília). Citação de um jornalista da Deutsche Welle: Baumann veio a Munique não apenas como um artista maduro, mas também com um conceito muito claro, uma grande dose de confiança em si mesmo.

Após o primeiro prémio, recebi muitas solicitações, concertos em Innsbrück, na NDR em Hamburgo, na minha orquestra em Estugarda, na Rádio de Baden Baden, em Basileia, em Paris na Radio de França, em Lisboa em Portugal ...

Na impossibilidade de manter uma posição de orquestra devido aos seus compromissos como solista, pensou então em ensinar, certo?

A Folkwang Musik Hochschule, em Essen, queria-me como professor. Houve um convite de Roma para uma apresentação como solista, mas eu não pude ir porque tinha a 6ªde Mahler com Claudio Abbado e eu não consegui tirar a semana de folga. Abbado perguntou-me por que eu não estava em Berlim. "Não há jeito, acabei de me demitir de Estugarda para ensinar em Essen!"

Pequena anedota: veio Maria Callas, ela tinha que cantar durante 17 minutos. No palco, quando finalmente chegou o seu momento havia uma tensão incrível, tocamos uma abertura, tocamos novamente uma abertura ... quando ela entrou, houve aplausos muito fortes, embora ainda não tivesse cantado um único som ...

Eu nunca esqueci isso!

Comecei a ensinar em 1967, por 12 anos. Um dia, recebi uma chamada da WDR pedindo-me que assumisse por uma temporada em Colónia, pois o trompa solo Erich Penzel estava de licença médica. Então eu toquei na Rádio de Colónia e ensinei em Essen. Num dos seguintes concertos desta orquestra, era necessário um trompista como solista ...

Deixando os críticos falarem após o concerto, o título foi: Baumanns Wunderhorn. Certamente não acontece com frequência que um solista de trompa voe para a glória e coloque na sombra um maestro como Sir John Barbiroli, mas esse foi o caso no 6º concerto da Rádio de Colónia. Neste programa, Hermann Baumann tocou o papel solista de Serenata de Benjamin Britten e foi lindo. É necessário ter cuidado com os superlativos, mas aqui eles estão no lugar certo. Perfeição e virtuosismo afastam tudo do que sabíamos até agora.

O que surpreendeu a todos na sua carreira é o número das suas gravações!

Duas vezes por ano, eu voava para Berlim Ocidental para gravar para a RIAS e SFB e depois seguiram-se gravações em Bremen, Hannover para a WDR e HR. Depois a Saarländischer Rundfunk, Kaiserslautern, Bayerische Rundfunk. Toquei no Concertgebouw em Amsterdão, sob a direção de Jaap Schröder, na Orquestra de Câmara de Karl Münchinger, em Viena no Consentus Musicus de Nicolaus Harnoncourt, seguido de gravações.

Antes do seu grave acidente em 1993, passou por períodos de dificuldade?

Em Munique eu era muito conhecido, mas ainda não tinha tocado com Karl Richter. Maurice André, que eu conhecia há anos, disse a Richter: tem que contratar Baumann de Estugarda.

Uma digressão a Itália e Suíça em 1966 viajando de comboio, foi uma experiência para todos nós. Em Modena, tivemos um ensaio de colocação antes de um concerto e Richter diz: a Ária do Quoniam, temos que tocá-la completa hoje à noite. Levantei-me e toquei a minha parte até ao fim e depois perguntei: tenho que mudar alguma coisa?

Karl Richter riu juntamente com toda a orquestra e o coro. E ele disse: é assim que eu sempre imaginei esta ária!

Durante esta viagem, Karl Richter perguntou-me: Quer tocar comigo na Goldenersaal em Viena?

... claro! (ele queria o 2º Concerto de R. Strauss)

Wunderbar!! (Maravilhoso!!)

Karl Richter diz: Será com a Sinfónica de Viena no ciclo "as grandes sinfonias".

Foi um longo inverno, no início de abril, fui às montanhas esquiar e andar de trenó. Caímos do esqui, eu e a minha filha Johanna. Ela não teve nada, mas eu tive. Com dores fomos ao hospital mais próximo. Eu fraturei um osso metacarpo na minha mão, tiveram que engessar. 18 dias antes do concerto em Viena! Mas não cancelei. Na Alexander colocaram-me um gancho no instrumento para que eu pudesse segurá-lo melhor, levantando o peso graças a uma alça em volta do meu corpo. Dia e noite, eu tentava libertar os meus dedos do gesso para poder praticar um pouco do meu 2ºConcerto de R. Strauss. Eu conduzi até à Áustria com a minha esposa, ainda usando uma tala. Estávamos no Hotel Imperial, com vista para a Goldenersaal. Richter olhou para mim um pouco cético quando descobriu o que me tinha havia acontecido, a orquestra o mesmo. O público olhou-me de forma engraçada quando subi ao palco. Sendo este 2º de Strauss particularmente difícil, no final, os vienenses exaltaram com alegria, deliciados com tal interpretação neste sala mítica de Viena.

Então o mundo abriu-se para mim, a minha agenda estava a ficar preenchida cada vez mais. Minha querida esposa não era apenas uma dona de casa com quatro filhos, como se ouvia muito na TV, mas estava o dia inteiro no escritório e ao telefone. Os seus estudos de latim e alemão ajudaram um pouco, mas depois o inglês e o francês ganharam preponderância.

A trompa natural, no que lhe diz respeito, também é uma bela história de amor ...

Os meus alunos gostavam de se encontrar para tocarem juntos (trechos orquestrais) Bach, Beethoven, até à música contemporânea. A música dos séculos XVIII e XIX era tocada com trompas naturais. Comecei a tocar trompa natural em 1967 e disponibilizava os meus próprios instrumentos aos meus alunos. Posteriormente, a Musik Hochschule de Essen comprou trompas naturais. O Folkwang Horn Ensemble fazia muitos pequenos concertos. Particularmente a Grande Missa de St. Hubert fez-me querer transcrevê-la. Uma obra de música festiva e de caça. Os andamentos variam de festivos, a contemplativos, alegres e carácter mais popular ... Fiz muitos concertos com este ensemble, a Meca dos trompistas. No final de cada concerto com a Grande Missa de St Hubert, 9 trompas naturais e 8 trompas de cilindros compartilhavam os aplausos.

Todos os anos eu regressava a Viena como solista, foram cerca de 20 vezes. Com Nikolaus Harnoncourt e o Consentus Musicus Wien, gravamos os 4 concertos de W.A. Mozart, na trompa natural. Em Oslo, ofereceram-me um lur. Em Copenhague, a rainha dinamarquesa Ingrid mostrou-me trompas com 300 anos encontradas em pântanos. Em 2005, em São Petersburgo, vi pela primeira vez trompas russas dos séculos XVII e XVIII. O que é incrível é que apenas se pode tocar um som! Espontaneamente, convidei o ensemble Russian Horn Capella para realizar concertos na Alemanha. Em outubro de 2006 eu fui solista, maestro e também apresentador. Na Itália, dirigia com frequência e tocava a trompa natural, por exemplo em Florença, com uma sinfonia de J. Haydn e depois tocava G.F. Handel, G.P. Telemann, J. Haydn ou W. A. Mozart. Acabávamos com uma bela sinfonia de W.A. Mozart.

Após os concertos de trompa, o público queria sempre ouvir como encore o meu G. Rossini na trompa natural e a chamada de Mozart no Kelp.

Sempre gostei de ir a Milão com o Carme Ensemble, uma soberba pequena orquestra de câmara. Uma digressão levou-nos ao sul da França e depois a Paris. Depois de J. Haydn - W.A. Mozart, o destaque do concerto era a Trompe de France (trompa de caça francesa). De Paris fomos diretos aos EUA. Em Ann Arbor, estava a Orquestra Gewandhaus com Kurt Masur, Anne Sophie Mütter e eu. Christoph von Dohnanyi levou-me a Cleveland e depois ao Carnegie Hall em Nova York com o 3º Concerto de W.A. Mozart. Esta foi a minha 33ª digressão nos EUA.

A expressão "Dar a volta ao mundo" encaixa-lhe perfeitamente!

Queriam ouvir a minha interpretação do 2º de R.Strauss em todo o lado: Varsóvia, Cracóvia, Katovice, Oslo, Bergen, Trondheim, Helsínquia, Tempere, Gotemburgo, Estocolmo, Malmo, Reiquiavique, Amsterdão, Roterdão, Haia, Belgrado, Paris, Estrasburgo, Lyon ...

Em quase todas estas cidades, eu dei masterclasses.

O meu querido Concertino de C.M. von Weber foi filmado no castelo Herrenchiemsee pela TV alemã para um programa. Depois, houve o concerto de domingo (Wie schön ist doch Musik!), um programa muito popular, toquei o 1º Concerto de R. Strauss. Em Munique toquei 3º e o 4º Concerto de W.A. Mozart para a TV, e em programas da Vienna 2 "trompa e piano".

A Orquestra de Câmara Württembergische acompanhou-me numa digressão à África do Sul (Cidade do Cabo, Pretória, Joanesburgo, Durban). Encontrei na praia uma alga marinha (Kelp - trompa africana), a qual eu toquei durante vários anos (incluindo a chamada de Mozart).

A digressão seguinte levou-nos à União Soviética, Moscovo, São Petersburgo, Riga. Com Handel, Haydn e Mozart.

Quase sem interrupção, fomos para os Estados Unidos.

No Festival "Mostly Mozart", toquei o 3º e o 4º Concertos e depois com o Tokyo String Quartet, o Quinteto Kv. 407 .

A Sinfónica de Viena contratou-me com o 1º Concerto de R. Strauss para o Festwochen im Mai, depois no Salzburger Festspiele, pediram-me 2 concertos, um antes do intervalo e outro depois!

Thea Dispeker passou a representar-me nos Estados Unidos e Canadá.

Em cada 3 anos ia ao Japão, no total foram 10 digressões de 3 semanas. Com a orquestra do NHK de Tóquio, o Konzerstück de R. Schumann, dirigido por Heinz Wallberg. Os concertos em Sapporo, Osaka, Kyoto e Tóquio foram sempre filmados pela televisão. A próxima viagem foi a Israel; com a Orquestra de Jerusalém, eu fui o herói da noite. Com a orquestra de câmara, fomos a Haifa e Telavive. Depois, uma digressão com a Camerata Sándor Végh em Paris e por toda a França.

As cordas da Filarmónica de Viena e do London Mozart Players acompanharam-me em digressões pela Alemanha.

Depois, 13 apresentações do Concertino de Weber em 14 dias com a Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie Herford.

Depois, o 4º Concerto de W.A. Mozart com a Filarmónica de Munique em Zurique, Basileia, Luzerna, Berna, Lausana e Genebra. E novamente em Nova Iorque, onde Thea Dispeker beijou-me a mim e à minha minha esposa de forma emocionada. Muitos produtores de concertos estavam impacientes. Pediam principalmente Mozart, de novo os 4 concertos de W.A. Mozart.

Desde 1964, tocava tudo de memória, tudo!

Havia também os encores: o último movimento, o rondo, mas desta vez numa trompa sem cilindros de Antoine Courtois, com dois séculos.

Depois, de Rossini, a Grande Fanfarra na minha própria versão para trompa natural, incluindo sons multifónicos.

De seguida a minha primeira de 3 viagens à Austrália. «Come blow your Horn, Hermann Baumann»

Na Austrália esperavam que eu, alemão, tocasse a trompa como um barítono italiano. A imprensa escreveu: a ABC deveria tentar agarrar este soprador de trompa novamente!

Durante a 2ª digressão (Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Sydney, Hobart e Perth), os organizadores alugaram um barco a vapor do Mississippi para a minha festa de aniversário, com outros trompistas que traziam as suas famílias.

Todo o mundo conhece as suas gravações com Kurt Masur e Pinchas Zukerman, como aconteceram?

Em 1983, em Dubrovnik, Croácia, na cidade velha, toquei com órgão e quem estava na plateia? Maestro Kurt Masur com o seu filho!

Algumas semanas depois, gravei em Leipzig R. Strauss e C.M. de Weber com a Gewandhausorchester.

Um ano depois, fizemos R. Glière, C. Saint-Saëns, P. Dukas e E. Chabrier. Depois quando regressei aos EUA com R. Glière na minha bagagem, tornou-se o novo "hit" para grandes orquestras (com trombone, tuba e harpa) 12 apresentações de R. Glière numa viagem. Sir Simon Rattle, já meu conhecido de um concerto em Copenhaga, fez uma digressão comigo na Inglaterra com o 3º Concerto de W.A. Mozart e o 1º Concerto de R. Strauss.

Em Nova York, com Pinchas Zukerman, toquei o trio Brahms e, em seguida, com a sua Orquestra de Câmara Saint Paul, fiz uma digressão e gravação dos 4 concertos de Mozart para a Philips. Depois, em Londres, a gravação com a Academia St Martin in the Fields dos concertos de J. Haydn e G.F. Telemann.

Os seus parceiros preferidos?

Os concertos com piano tornaram-se cada vez mais populares. Horn und Kavier

Na América e no Canadá o meu pianista era Samuel Sanders, que também tocava regularmente com S. Rostropovich. Na Europa, foram Leonard Hokanson, Pi-Hsien Chen e Catherine Vickers.

Situações estranhas ou incongruentes na sua vida?

Uma Masterclasse em Berna para trompistas de todo o mundo era um bom exemplo do que se esperava de mim: fazer a trompa brilhar como solista, libertá-la do peso e dar-lhe a atratividade de um instrumento solo. Em Berna e em Gstaad-Saarnen no Festival Yehudi Menuhin, toquei W.A. Mozart e Otmar Schoeck! Numa conversa com J. Menuhin, ele perguntou-me se poderíamos tocar o trio Brahms com trompa alpina!

Em Sydney, toquei com um Didgeridoo.

A orquestra estudantil de Tubingen e eu recebemos um convite de Dresden em 1964. Fomos de autocarro para Dresden e tivemos um concerto no Dresdener Zwinger, mas não havia audiência apenas aqueles que nos acompanharam por acaso ...

Nós tivemos o nosso espetáculo nos média em silêncio. Na outra parte do Zwinger, vimos as luzes das festividades dos 15 anos da RDA!

Por favor, conte-nos as circunstâncias do seu terrível acidente.

Em 1993, a noite de 9 de janeiro foi uma típica da minha vida, toquei o 2º Concerto de R. Strauss com a Orquestra Filarmónica de Buffalo. O concerto foi bom, tive boas críticas. Depois do concerto, fui convidado para jantar, e no dia seguinte tinha que voltar para Dusseldorf. Durante a noite, tive um enfarte (apoplexia). Fiquei sem conseguir andar ou falar. Ainda hoje é difícil. Somente depois de alguns anos, eu pude tocar novamente; muito tempo durante o qual lutei. Mas há pessoas que acreditam em nós. Thea Dispecker disse-me: Você tem que regressar ao palco. Os primeiros concertos não foram muito bonitos, mas estavam a melhorar. Pensei em José Carreras, com quem eu havia feito um concerto em Lucerna em 1990, José superou uma leucemia. Isso deu-me força.

Desde então, tenho feito concertos em vários países: Suíça, Turquia, Espanha, Itália, Bulgária, Israel, Japão, Coreia, América, Brasil, Argentina, Alasca, Canadá, Islândia, Rússia, Sérvia, República Checa, Croácia, Bélgica, França, Portugal, Áustria, Grécia, China, Finlândia…

Mestre, você tem algum comentário final?

Aqui está uma passagem da minha biografia escrita pela minha esposa Hella, que morreu 2 anos após o meu acidente: ele toca trompa como se expressa um grande cantor. Não é apenas a técnica que cria a arte de Hermann Baumann, mas sua capacidade de assumir papéis diferentes: a trompa certamente possui uma grande variedade de caracteres, cores e atmosferas. Um ataque metálico e decidido, um sentimento heroico, o canto dramático, o idílico de um lied, um passado melancólico, o Sarastro festivo e sério, mas também a deliciosa ironia de Till Eulenspiegel.

O New York Times uma vez escreveu: um trompista como ele nasce se tivermos sorte uma vez em cada século.

JULHO 2020

Tradução portuguesa J.Bernardo Silva

THANKS TO JUSTIN SHARP

Discography:

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Hornkonzerte Hornkonzert Es-dur KV 447 / Hornkonzert Es-dur KV 417 / Hornkonzert D-Dur KV 412/ Hornkonzert Es-Dur KV 495 St. Paul Chamber Orchestra – Pinchas Zuckerman

- Virtuose Hornkonzerte Reinhold Glière: Konzert B-Dur Camille Saint-Saens: Morceau de concert op. 94 Emmanuel Chabrier: Larghetto Paul Dukas: Villanelle für Horn und Orchester František Xaver Pokorný: Konzert D-Dur Gewandhausorchester Leipzig – Kurt Masur Academy of St.Martin in the Fields – Iona Brown

- Trio für Violine, Horn und Klavier / Passacaglia ungherese / Hungarian Rock / Continuum / Monument, Selbstportrait, Bewegung von György Ligeti mit Saschko Gawriloff – Violine / Eckart Besch – Klavier / Elisabeth Chojnacka – Cembalo / Bruno Canino und Antonio Ballista – Klavier

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Hornkonzerte Konzert Nr. 1 in D-Dur KV 388b (412/514), Konzert Nr. 2 in Es-Dur KV 417, Konzert Nr. 3 in Es-Dur KV 447, Konzert Nr. 4 in Es-Dur KV 495 Concentus Musicus Wien (auf Originalinstrumenten)- Nikolaus Harnoncourt

- Commercial LP Recordings – Schallplatten-Einspielungen:

- Abendlieder, Liebeslieder und Romanzen von Benediikt Randhartinger Schlummerlied mit Klesie Kelly, sopran; Ian Patridge, tenor; Hermann Baumann, horn; Werner Genuit, klavier 1977 EMI 1 C 065-10 731

- Bayern´s Schlösser und Residenzen * Oettingen-Wallerstein Konzerte Von Rosetti und Reicha, Kammermusik Von Nisle und Amon – Rosetti, Konzert F-dur für Horn und Orchester. Hermann Baumann, Concerto Amsterdam, Leitung Jaap Schröder, Johann Andreas Amon, Quartett F-dur für Horn, Violine, Viola, Violoncello. Hermann Baumann, horn; Jaap Schröder, Violin; Wiel Peter, viola; Anner Bylsma, violoncello 1973 BASF 29 21189-4

- Bayern’s Schlösser und Residenzen * Würzburg Kammermusik und Konzerte von Friedrich Witt, Joseph Fröhlich, Joseph Küffner, Friedrich Witt, Konzert F-dur für 2 Hörner und Orchecster. Hermann Baumann, Mahir Cakar, horn; Concerto Amsterdam, Leitung Jaap Schröder 1973 BASF 29 21194-0

- Bayern’s Schlösser und Residenzen * Thurn und Taxis Konzerte von Hoffmeister, Pokorny, Schacht, und Abel Franz, Xaver Pokorny, Concerto F-dur für 2 Hömer, Streichorchester und 2 Fötten. Hermann Baumann, Christoph Kohler, horn; Concerto Amsterdam, Leitung Jaap Schröder 1973 BASF 29 21191 -6

- Bayern’s Schlösser und Residenzen * Augsburg Konzerte von Leopold Mozart, Kammermusik Von Bühler und Graf – Leopold Mozart, Konzert Es-dur für 2 Hörner, Streicher und Basso continuo. Hermann Baumann, Mahir Cakar, horn. Sinfonia di Camera D-dur für Horn, Violine, 2 Violen und Basso continuo. / Hermann Baumann, horn; Jaap Schröder, violine. / Sinfonia da Caccia G-dur für 4 Hörner, Streicher, Pauken und Basso continua. Hermann Baumann, Christoph Kohler, Mahir Cakar, Jean-Pierre Lepetit, horn / Concerto Amsterdam, Leitung Jaap Schroder 1973 BASF 29 21195-9

- Bayern’s Schlösser und Residenzen * Augsburg – H. Backofen Konzert F-dur. Concerto Amsterdam; Leitung Jaap Schröder 1973 BASF 29 211 93-2

- Johannes Brahms Trio Es—Dur für Klavier, Violine, und Waldhorn, Op. 40 Malcom Frager, klavier; Stoika Milanova, violine; Hermann Baumann, horn 1971 MP8 168 007 1971 MP8 BASF 2521184 -3

- Beethoven – Rossini – Strauss — Czerny – Krufft / Works for Horn and Piano / Karl Czerny, Andante e Polacca; Beethoven, Sonata in F, Op. 17; Rossini, Prelude, Theme et Variations; Von Krufft, Sonata in E; R. Strauss, Andante Op. posth. Hermann Baumann, Leonhard Hokanson 1986 Philips 416 816-1

- Concertos: Abrechtsberger, Wagenseil, M. Haydn / M. Haydn, Adagio und Allegro molto für Horn, Altposaune und Orchester. Armin Rosin, posaune; Hermann Baumann, horn; Philharmonia Hungaria; Dirigent Yoav Talmi 1979 Telefunken 6.42419 AW

- Aerztliche Doppelbegabung Fa. Sandoz (Arznei-Fabrik) Alexander Borodin für Horn und Klavier: Nocturne, Masurka, Intermezzo, Reviere, Serenade. Hermann Baumann, horn; Eckhard Besch, klavier / Kleine Platte (17 cm) Contra Copyr TST78032

- Die schönsten Konzerte, W. A. Mozart / Konzert für Horn and Orchester Nr. 3 Es-dur KV 447. Mozarteum-Orchester Salzburg; Dirigent Leopold Hager 1979 Teldec Telefunken noblesse 6.48188 DM

- Franz Schubert und seine Freunde Consortium classicum Franz Schubert, Auf dem Strom, D. 943. Ian Partridge, tenor; Werner Genuit, klavier; Hermann Baumann, horn 1977 EMI Electrola GmbH I C 151-30 736/39 Q

- Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow, Zwei Kantaten Lobe den Herrn, meine Seele; Kantate für Soli, Chor, 2 Hörner und Orchester. Hermann Baumann, Willy Rütten, horn; Heinrich-Schütz-Chor Heilbronn; Südwestdeutsches Kammerorchester Pforzheim; Leitung Fritz Werner 1964 Erato * Christophorus CGLP 75834

- Georg Philipp Telemann Violinsuite F-dur. Hermann Baumann, Adriaan van Woudenberg, horn; Concerto Amsterdam; Gustav Leonhardt, cembalo; Dirigent Frans Brüggen 1967/68 Das alte Werk Telefunken royal sound SAWT 9541 -B

- Georg Philipp Telemann, Tafelmusik Teil III / Konzert Es-dur für 2 Hörner, Streicher und Basso continuo. Hermann Baumann, Adriaan van Woudenberg, horn; Concerto Amsterdam; Leitung Frans Brüggen 1965 Teldec Telefunken-Decca TK 11564/ 1-2

- Georg Philipp Telemann, Tafelmusik / Konzert Es-dur für 2 Hörner, Streicher und Basso continuo. Adriaan Van Woudenberg, Hermann Baumann, horn; Concerto Amsterdam; Leitung Frans Brüggen 1966 HOR ZU Teldec SHZT 526 Ste LP 071 297

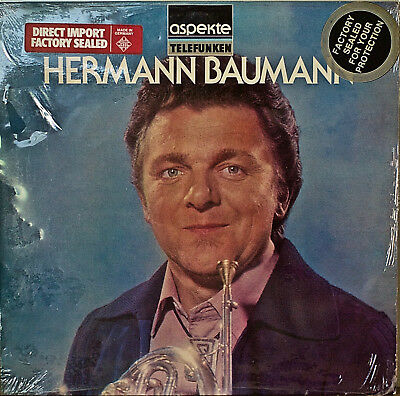

- Händel Concerto grosso Nr. 29 F-dur für Horn und Orgel. Rosetti Hornkonzert d-moll; Haydn Hornkonzert Nr. 1 D- dur. Hermann Baumann, horn; Herbert Tachezi, orgel; Concerto Amsterdam; Konzertmeister Jaap Schröder Teldec 642 326 AH Aspekte, 1969/ 1975 MC 442 326

- Händel, Concerto grosso Nr. 29 F-dur, für Horn und Orgel. Telemann, Konzert für Horn und Orchester D-dur. Corelli, Sonate für Horn (Violine) und Basso continuo Nr. 5 g-moll Op. 5. / Förster, Konzert für Waldhorn umd Orchester Es-dur. Hermann Baumann, horn; Herbert Tachezi, orgel 1975 Teldec 641 932 AW, MC 441 932 CX

- G. F. Händel Juilius Caesar / Münchener Bachchor und -orchester; Leitung Karl Richter; Arie mit obl. Horn; Fischer Dieskau, Hermann Baumann 1970 DGG 2711 009

- Haydn, Hornkonzerte Nr. 1 und Nr. 2. / Danzi, Hornkonzert E-dur; Rosetti, Hornkonzerte d-moll, Es-dur; Mozart, Hornkonzert Es-dur KV 417. Concerto Amsterdam; Konzertmeister Jaap Schröder 1966/1969 Teldec 635 057 DC (2 LP)

- Hermann Baumann, Music for Horn by Leopold Mozart, Francesco Antonio Rosetti, Johann Andreas Amon Concerto Amsterdam; Jaap Schröder, conductor 1978 hnh records 4033, 1972/ 1973 Acanta Stereo 20 227 529

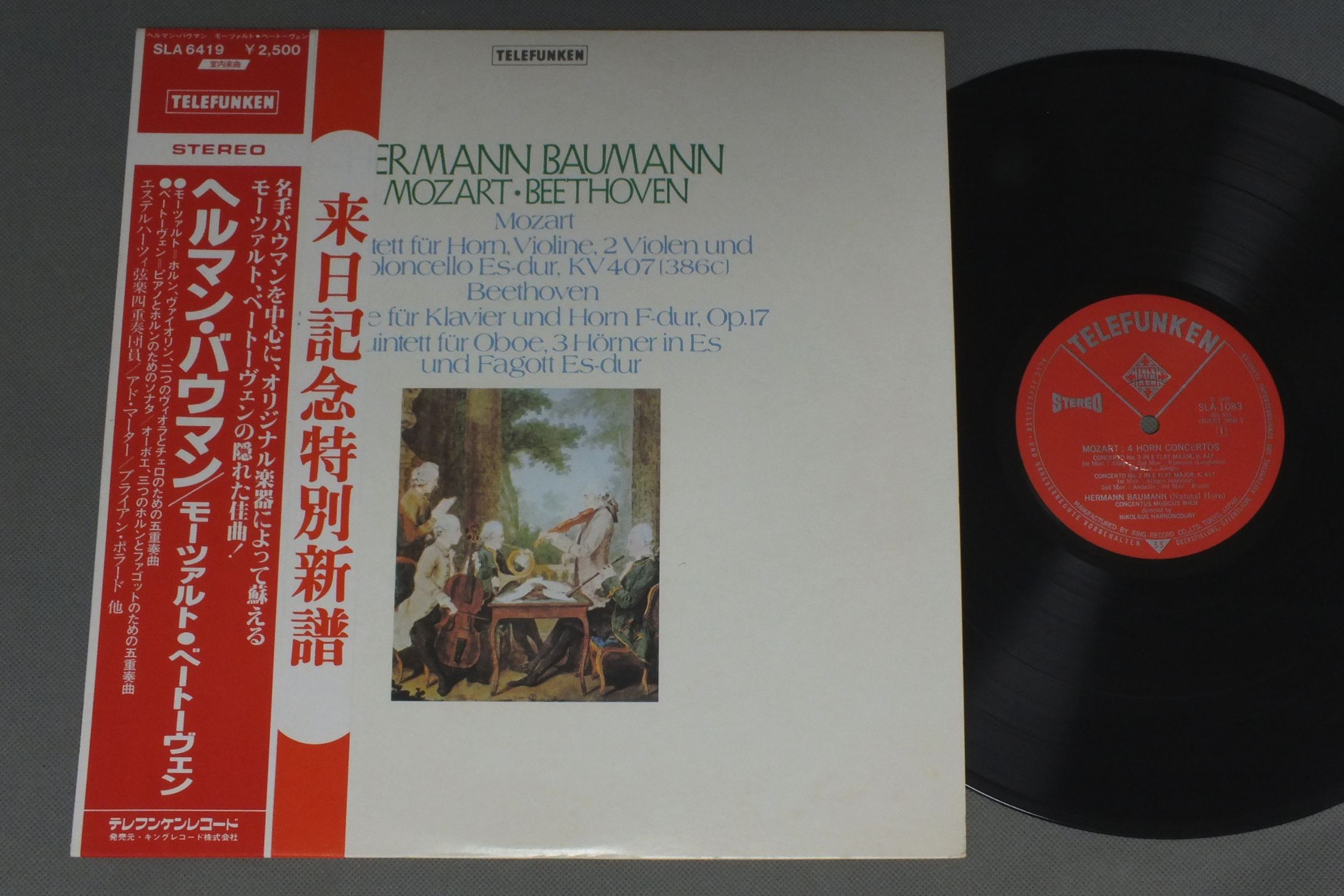

- Hermann Baumann, Mozart, Beethoven Mozart Quintett für Horn, Violine, 2 Violen und Violon-cello, Es-dur, KV 407. Beethoven Sonate für Klavier und Horn F-dur Op. 17. / Beethoven Quintett für Oboe, 3 Hörner in Es und Fagott Es-dur. Hermann Baumann, Adriaan van Woudenberg, Werner Meyenclorf, naturhorn; Mitglieder des Quartetto Esterhazy; Stanley Hoogland, hammerflügel, Ad Mater, oboe; Brian Pollard, fagott 1979 Telefunken SLA 6419

- Hermann Baumann – Händel Concerto grosso Nr. 29 F-dur. Antonio Rosetti Konzert d-moll für Horn und Orchester. / Joseph Haydn, Konzert Nr. I D-dur für Horn und Orchester Hob. VIId Nr. 3. / Hermann Baumann, horn; Herbert Tachezi, orgel; Concerto Amsterdam; Konzertmeister Jaap Schröder 1978 Teldec Telefunken-Decca 6.42326 AH

- Hornkonzerte Haydn, Mozart, Rosetti, Danzi: Haydn Konzert für Horn und Orchester Nr. 1 D—dur. / Danzi Konzert für Horn und Orchester E-dur. / Rosetti Konzert für Horn und Orchester d-moll. / Rosetti Konzert für Horn und Orchester Es-dur. / Haydn Konzert für Horn und Orchester Nr. 2 D-dur. / Mozart Konzert für Horn und Orchester Nr. 2 Es-dur, KV 417. - – Concerto Amsterdam; Konzertmeister Jaap Schröder 1969 Teldec TK 11 540/ 1-2 6.35057 DX

- Hornkonzerte Von Danzi, Rosetti & Haydn: Haydn Konzert Nr. 1 D-dur für Horn und Orchester. Danzi Konzert für Horn und Orchester E-dur. Rosetti Konzert d-moll für Horn und Orchester. Concerto Amsterdam; Konzertmeister Jaap Schröder 1969 Telefunken Royal Sound Stereo SAT 22 516 - 1969 Telefunken (Das alte Werk) Reference 6.41288 AQ

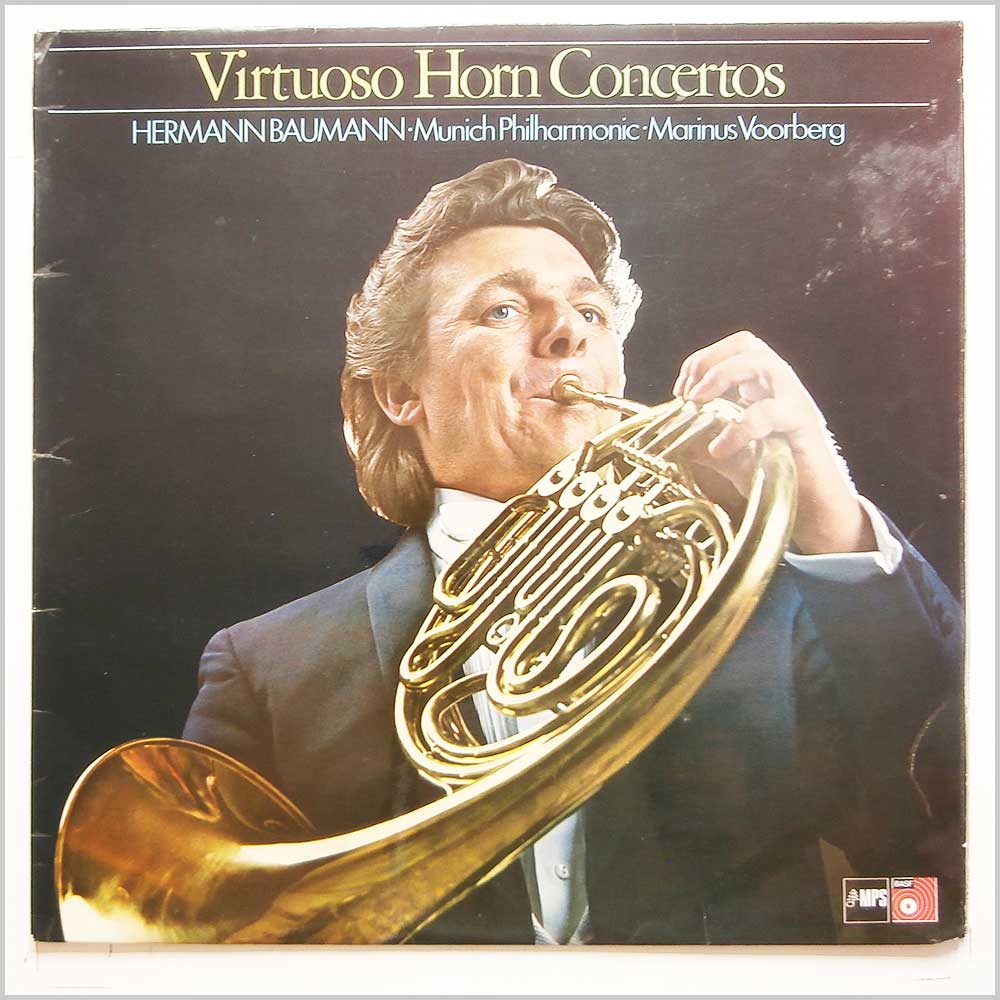

- Hornkonzerte der Romantik: Schumann Konzertstück F-dur Op. 86 für 4 Hörner und grosses Orchester. / Schoeck Konzert D-moll Op. 65 für Horn und Streichorchester. /Weber Konzert E-moll Op. 45 für Horn und Orchester. / Hermann Baumann mit Mahir Cakar, Werner Meyendorf, Johannes Ritzkowsky, und Jean-Pierre Lepetit; Wiener Symphoniker; Dirigent Dietfried Bernet 1969 MP5 168 015, 1970 BASF CRO 834 MPS 13005 St

- Horn und Orgel: Telemann-Corelli-Hände1-Förster / Hermann Baumann, Herbert Tachezi – 1975 Telefunken 6.41932 AW, 1984 Teldec 66.235474 1976 Telefunken SLA 1092

- Italienische Solokonzerte (um 1700 Musik und ihre Zeit) Torelli, Vivaldi, Locatelli: Vivaldi, Konzert für 2 Hörner, S trezcher und Continuo F-dur. Hermann Baumann, Adriaan Van Woudenberg, horn; Concerto Amsterdam; Konzertmeister Jaap Schröder 1966 Telefunken Royal Sound Stereo (Das alte Werk) SAWT 9499-A / 1966 Telefunken (Das alte Werk) Reference 6.41217 AQ

- Jahrhunderthalle Farbwerke Hoechst Ausgewählte Veranstaltungen: Tschaikowski, C. M. von Weber, Britten, W. A. Mozart, Hornkonzert Nr. 4 Es-dur KV 495 Romanze, Rondo. 1965

- Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburgische Konzerte Nr. 2 F-dur BWV 1047. / Nr. 4 G—dur BWV 1049. / Nr. 1 F-dur B WV 1046 (`a 2 Corni di Caccia, 3 Hautbois, `e Bassono, Violino piccolo concertato, 2 Violini, una Viola & Violoncello, col Basso Continuo). / Nr. 3 G-dur BWV 1048. / Nr. 6 B-dur, BWV 1051. Nr. 5 D- dur BWV 1050. // Original instruments; Hermann Baumann, Marcus Schleich, corno (handhorn); Concentus Musicus Wien; Leitung Nikolaus Harnoncourt 1982 Teldec Telefunken – Decca 4. 35620-00-501 // 1982 Das Alte Werk, Teldec 6.35620 FID

- J. S. Bach 6 Bandenburgische Konzerte: Münchener Bachorchester; Leitung Karl Richter; Hermann Baumann, Werner Meyendorf, horn 1970 DGG 2708 013

- J. S. Bach Bandenburgische Konzerte 1, 3, 6 – - -DGG 198 487

- J. S. Bach Weihnachtsoratorium: Lübecker Knabenkantorei; Leitung Hans-Jürgen Willie; Elly Ameling, sopran; Helen Watts, alt; Peter Pears, tenor; Tom Krause, bass; Hermann Baumann, Willy Rütten, horn; Stuttgarter Kammerorchester; Dirigent Karl Münchinger 1968 Decca SET 346

- Johann Sebastian Bach Weihnachtsoratorium BWV 248 Teil IV / Regensburger Domspatzen, Collegium St. Ermmeram; Hermann Baumann, Ab Koster, corno (handhorn); Leitung Hanns-Martin Schneidt // 1979 Archiv Produktion 2723 057, 2710 024

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Der zufriedengestellte Äolus Nr. 1; 2; 11; 15. // Concentus Musicus Wien; Leitung Nikolaus Harnoncourt // 1983 Teldec 6.42915 AZ Das alte Werk

- Das Schaffen Johann Sebastian Bachs: „Wie schün leuchtet der Morgenstern“, BWV 1. // Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, bariton; Edith Mathis, sopran; Ernst Haefliger, tenor; Hermann Baumann and Werner Meyendorf, horn; Münchener Bach-Chor; Münchener Bach-Orchester; Dirigent Karl Richter Achiv 198 465 (1968)

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Das Kantatenwerk Vol. 1: Kantate I, ”Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern” BWV 1 Nr. 1; 6. Concentus Musicus Wien, mit Originalinstrumenten; Gesamtleitung Nikolaus Harnoncourt 1971, Teldec Te1efunken—Decca SKW 1/ 1-2 BR 2

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Das Kantatenwerk: Kantate BWV 140 am 27. Sonntag nach Trinitatis ”Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme.” Der Süddeutsche Madrigalchor, Das Consortium musicum; Dirigent Wolfgang Gönnenwein ca. 1973 Electrola, EMI, SME 91 658

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Das Kantatenwerk Vol. 7: Kantate 24 ”Ein ungefärbt Gemüte” BWV 24 Nr. 3 Coro, Nr. 6 Choral. / Kantate 27 ”Wer weiss, wie nahe mir mein Ende” BWV 27 Nr.1 Coro, Nr. 6 Choral. // Concentus Musicus Wien mit Originalinstrumenten; Gesamtleitung Nikolaus Harnoncourt 1973 Teldec SKW7/ 1-2 BR 2

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Das Kantatenwerk ”Gott, der Herr ist Sonn’ und Schild” BWV 79. Der Süddeutsche Madrigalchor, Consortium musicum; Dirigent Wolfgang Gönnenwein 1967 Electrola EMI SME 91 657

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Kantaten: Sonntage nach Trinitatis vom 6. Sonntag bis zum 17. Sonntag nach Trinitatis ”Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht” Kantate zum 9. Sonntag nach Trinitatis BWV 105, Nr. 5. Arie (Tenor) (Hermann Baumann) ”Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan” Kantate zum 15. Sonntag nach Trinitatis BWV 100, Nr. 1. Chor (Hermann Baumann, Christoph Brandt) ” Wer weiss, wie nahe mir mein Ende” Kantate zum 16. Sonntag nach Trinitatis BWV 27, Nr. 1. Chor (Hermann Baumann) Münchener Bach-Chor, Münchener Bach-Orchester; Dirigent Karl Richter Archiv Production 2564 172/3 1978 Polydor International GmbH

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Das Kantatenwerk (14, 16) Vol. 4: Kantate 14 ”Wär Gott nicht mit uns these Zeit,” BWV 14, N r. 1. Coro; N r. 2. Aria (Soprano); Nr. 5. Choral (Coro). Kantata 16 ”Hcrr Gott, dich loben wir” BWV 16, Nr. 1. Coro; Nr. 3. Aria (Basso) und Coro, Nr. 6. Choral (Coro). // Das verstarkte Leonhardt-Consort mit original- instrumenten; Corno da caccia, Hermann Baumann; Gesamtleitung Gustav Leonhardt 1972, 2/ 1975 Teldec Telefunken-Decca 6.35030-00-501 (SKW 4/ 1-2 BR 2)

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Das Kantatenwerk (52) Vol. 14 Kantate 52 ”Falsche Welt, dir trau´ ich nicht” BWV 52 Nr. 1. Sinfonia; Nr. 6. Choral. // Das Verstarkte Leonhardt-Consort mit originalinstrumenten; Hermann Baumann, Ab Koster, corno (handhorn); Gesamtleitung Gustav Leonhardt 1976 Teldec Telefunken-Decca 6.35304—00 501 (SKW 41 / 1-2 BR 2)

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Kantaten: ”Wer weiss, wie nahe mir mein Ende” BWV 27. ”O Jesu Christ, mein’s Lebens Licht” BWV 118 für Chor, Horn, Zink oder hohe Trompete, Posaune, Orgel. Concerto Amsterdam; Konzertmeister Jaap Schröder 1966/ 67 royal sound Stereo Teldec ”Telefunken-Decca” SAWT 9489-B

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Kantaten: ”Was soll ich aus dir machen, Ephraim” BWV 89 für Soli: Sopran, Alt, Bass; Chor; Oboe I / II; Horn; Violine I / II; Viola; Continuo. // Leitung Joachim Martini (Nr. 89); Monteverdi-Chor Hamburg; Leitung Jürgen Jürgens (N r. 90 u. 161); Con- certo Amsterdam, Konzertmeister Jaap Schröder 1965 royal sound Stereo SAWT 9540-B Das Alte Werk

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Les grandes Cantates de J. S. Bach Cantate BWV 79, ”G0tt, der Herr ist Sonn’ und Schild” pour la Fete de la Reformation, Nr. 1, 3, 6. // Chorale Heinrich Schütz de Heilbronn, Orchestre de Chambre de Pforzheim; Hermann Baumann, Willy Rütten, horn; Direction Fritz Werner 1966 Erato Artistique – Gravure universelle STU 70 222

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Les grandes Cantates de J. S. Bach: Cantate BWV 1 ”Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern” Nr. 1. Chorale Heinrich Schütz de Heilbronn, Orchestre de Chambre de Pforzheim; Hermann Baumann, Willy Rütten, horn; Direction, Fritz Werner 1966 Erato Stu 70 284 Artistique Gravure universelle

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Les grandes Cantates de J. S. Bach: Cantate BWV 118, ”O Jesu Christ, mein’s Lebens Licht” pour choeur, 3 hautbois, 2 cors, basson, orchestre a cordes et continuo. // Chorale Heinrich Schütz de Heilbronn, Orchestre de Chambre de Pforzheim; Hermann Baumann, Willy Rütten, horn; Direction Fritz Werner 1965 Gravure Universelle Erato STU 70 342

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Les grandes Cantates de J. S. Bach Cantate BWV 40, ”Dazu ist erschienen der Sohn Gottes” Nr. 1, 7. Chorale Heinrich Schütz de Heilbronn; Orchestre de Chambre de Pforzheim; Direction Fritz Werner 1964 Erato Stereo STE 50 223 Artistique

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Les grandes Cantates de J. S. Bach: Cantate BWV 118, ”O Jesu Christ, mein’s Lebens Licht” pour choeur, 3 hautbois, 2 cors, basson, orchestre a cordes et continuo. // Chorale Heinrich Schütz de Heilbronn, Orchestre de Chambre de Pforzheim; Hermann Baumann, Willy Rütten, horn; Direction Fritz Werner 1965 Gravure Universelle Erato STU 70 342

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Les grandes Cantates de J. S. Bach: Cantate BWV 40, ”Dazu ist erschienen der Sohn Gottes” Nr. 1, 7. // Chorale Heinrich Schütz de Heilbronn; Orchestre de Chambre de Pforzheim; Direction Fritz Werner 1964 Erato Stereo STE 50 223 Artistique

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Les grandes Cantates de J. S. Bach ”Also hat Gott die Welt geliebt” BWV 68 Nr. 1. // Chorale Heinrich Schütz de Heilbronn; Orchestre de Chambre de Pforzheim; Direction Fritz Werner 1963 Erato LDE 3281 STE 50181 Artistique

- End of what I have copied at this time….Day 1 of work

- Konzerte für 2 Horner, Hermann Baumann: Leopold Mozart, Konzert Es—dur für 2 Hörner, Streicher und Basso continuo. Hermann Baumann, Mahir Cakar, horn // Franz Xaver Pokorny Concerto F-dur für 2 Hörner, Streichorchester und 2 Flöten. Hermann Baumann, Christoph Kohler, horn // Friedrich Witt Konzert F-dur für 2 Hörner und Orchester. Hermann Baumann, Mahir Cakar, horn // Concerto Amsterdam; Conductor Jaap Schröder 1972/ 73 BASF Stereo 20 22433-3 1972 / 73 Fono team, Acanta DC 22 433, MC DF 22 433

- Leopold Mozart, Sinfonia di caccia G-dur für 4 Hörner, Streicher, Pauken und Basso continuo. // Rossler (Rosetti), Konzert F-dur für Horn und Orchester. // Leopold Mozart, Sinfonia di Camera für Horn, Violine, 2 Violen, und Basso continuo. // Amon, Quartett F-dur für Horn, Violine, Viola und Violoncello. Hermann Baumann, Mahir Cakar, Christoph Kohler, Jean-Pierre Lepetit; Concerto Amsterdam; Konzertmeister Jaap Schröder 1972/73 Fono Team, Acanta DC 22 752, MC DF 32 752

- Ludwig van Beethoven Kammermusik des jungen Beethoven auf Originalinstrumenten 1792-1800 // Sonate für Klavier und Horn, F-dur Op. 17 // Quintett für Oboe, 3 Hörner in Es und Fagott in Es-dur – Ad Mater, oboe; Brian Pollard, fagott; Hermann Baumann, Adriaan van Woudenberg, Werner Meyernclor, naturhorn; Stanley Hoogland, hammerflügel – 1977 Telefunken, Das alte Werk royal 50111161 Stereo SAWT 9547-A

- Luigi Boccherini: Cellokoncerte C-dur Nr.1 & 2. Anner Bylsma, Violoncello; Hermann Baumann, Adriaan van Woudenberg, Horn; Concerto Amsterdam, Konzertmeister; Jaap Schröder 1965 Telefunken, Das alte Werk, Reference 6.41197 AQ

- Mozart Die 4 Hornkonzerte. Mozarteum-Orchester Salzburg Dirigent Leopold Hager 1986 Teldec 642 360 AW, MC 442 360 CX (1978) Teldec aspekte 6.43320 AH

- Mozart Die 4 Hornkonzerte: Concentus Musicus Wien; Leitung Nikolaus Harnoncourt (Serie ”Das alte Werk”) 1973 Teldec 641 272 AW, MC 441 272 CX

- Mozart: Hornquintett KV 407 – Hermann Baumann, horn; Strauss—Quartett 1964 Telefunken Royal Sound Stereo SLT 43 090-B

- Mozart Hornquintett Es—dur, KV 407 Quartetto Esterhazy, original instruments 1977 Das Alte Werk, Telefunken 6.42173 AW

- Mozart, Haydn, Sinfonia Concertante Mozart Sinfonia Concertante in E flat Major, K. 297b Württembergisches Kammerorchester Heilbronn; Jörg Farber, conductor 1964 Vox Pl.14.180

- Mozart Symphonie concertante KV 297B in Es-dur für Flöte, Oboe, Horn, Fagott und Orchester. Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields; Conductor, Neville Marriner 1984 Philips 411 134-1

- Originalinstrumente: Horn. Werke Von J. S. Bach, Beethoven, Mozart // Mozart Hornkonzert Nr. 1 D-dur (Allegro). Concentus Musicus Wien; Conductor Nikolaus Harnoncourt // Mozart Quintett für Horn, Violine, 2 Violen und Violoncello Es-dur. // Mitglied er des Quartetto Esterházy und das verstarkte Leonhardt-Consort; Conductor, Gustav Leonhardt // J. S. Bach Kantate ”War Gott nicht mit uns these Zeit,” BWV 14. Aria (Soprano), “Unsre Stärke heisst zu schwach.” Das verstärkte Leonhardt-Consort mit originalinstrumenten; Conductor, Gustav Leonhardt // Kantate ”Ein ungefärbt Gemüte” BWV 24. Coro ”A11es nun, das ihr wo11et.” Wiener Sängerknaben, Leitung Hans Gillesberger; Concentus Musicus Wien; Leitung Nikolaus Harnoncourt _ 1973 (Serie ”Das Alte Werk”) Teldec 642 321 AP MC 442 321. CR (1969-1977)

- Saverio Mercadante (1795-1870) // Concerto in Re Minore per Corno e Orchestra da Camera. Hermann Baumann, corno; The Masterplayers; Direttore Richard Schumacher 1978 Italia Fonit Cetra Itl 700 29 Stereo HiFi

- Stamitz: Hornkonzert E-dur.: Johann Michael Haydn Concertino D-dur // Teyber Konzert Es-dur. Philharmonia Hungarica; Dirigent Yoav Talmi 1978 Teldec 642 418 AW, MC 442 418 CX